Professor John Street argues that young people are much less alienated from, and indifferent to, politics than is widely supposed. They can also learn much about politics from famous campaigners.

Boris Johnson is more popular than David Cameron, we are told, because he makes us laugh. New Labour changed its policy on the immigration rights of ex-Gurkha soldiers because of the advocacy of the actress Joanna Lumley. In the UK and the US, Vivienne Westwood, Yoko Ono and Matt Damon warn against fracking –there’s even a Celebrities Against Fracking website. And in Russia, President Putin backed the imprisonment of Pussy Riot because they were a threat to his power.

Whatever we think about these examples, and the evidence presented to support them, they share one thing in common: the idea that politics is changing. It is becoming more ‘popular’. Not, of course, in the sense that politicians are well liked or that political parties are being deluged by enthusiastic supporters. They are not, in either case. What is happening, however, is that politics is becoming ever closer to popular culture, whether in the guise of Joseph Nye’s soft power or ‘celebrity politicians’ (Sharon Stone was recently honoured by a Nobel panel for her work on HIV/AIDS).

But as this conventional wisdom envelops our view of the political realm, we would do well to stop and ask what is really going on? Do we really take note of what actors say about issues of national and global importance? Do they actually represent us in the way they claim?

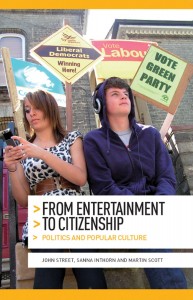

These questions lay behind research, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, that we conducted at the University of East Anglia and present in a new book, From Entertainment to Citizenship: Politics and Popular Culture. Our focus was on young people – 17-18 year olds, those just about to assume their role as fully-fledged citizens. Do they – the typical consumers of popular culture – learn anything about the world and its politics from their consumption of popular culture? Did they see the stars of films and music as speaking for them? The answers we got told a much more mixed and confused story than the headlines tend to convey.

First, there are the young people themselves. They are much less alienated from, and indifferent to, politics than is widely supposed – but also less invested in popular culture and its icons than people think. They are neither ‘dupes’ nor ‘dopes’ of media corporations. Actually, they are discerning and clever readers of the messages with which they are bombarded. They are ‘media savvy’ – all those lessons in media studies are not wasted.

At the same time, the young people we spoke to – in focus groups and individual interviews – did see popular culture as telling them about the their world. From the soaps they watched and the video games they played, they claimed to learn about how the world was run. From shows like the Apprentice and Britain’s Got Talent, they got a sense of how to succeed in a competitive world.

And finally, did they listen to those stars and celebrities who told them what to think and claimed to speak for them? Well, yes, sometimes. It was not, though, the rightness of the cause or the expertise of the stars that persuaded them. It was more matter of the ‘authenticity’ of the performer and the performance. This meant that they would listen to musicians who seemed to speak from their own experience, or who had proved themselves. This meant that Coldplay scored higher than Bob Geldof, and Simon Cowell higher than Bono. However dubious such judgements seem, they should not obscure the fact that popular culture can engage young people with politics, and can provide a route by which political values and ideas are negotiated.

John Street is professor of politics at the University of East Anglia. He is the author of several books, including Music and Politics, Politics and Technology, Rebel Rock: the politics of popular music, Politics and Popular Culture, and Mass Media, Politics and Democracy, and is co-editor of the Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock. He also wrote music reviews for The Times for over ten years. Entertainment to Citizenship: Politics and Popular Culture, by John Street, Sanna Inthorn and Martin Scott, is published by Manchester University Press.

This post originally appeared on www.politics.co.uk. Photo credit: Esten Hurtle.