Robert James Nicholls, University of East Anglia

Across the world, many cities are slowly sinking. Most are on the coast, including tropical megacities like Jakarta in Indonesia or Manila in the Philippines, or places like New Orleans, Vancouver or much of the Netherlands. Other sinking cities, like Mexico City and many of those in China, can be well inland. Yet this still remains a widely overlooked hazard.

In my three decades assessing this topic, I have reviewed evidence of subsidence in cities around the world. The problem is especially significant in Asia, where about 60% of the world’s population lives and the cities are growing rapidly. However, some cities have also shown there are things that can be done to stop subsidence.

The problem is illustrated by a recent study by researchers in China which found that more than a third of the country’s urban population – some 270 million people – live in sinking cities.

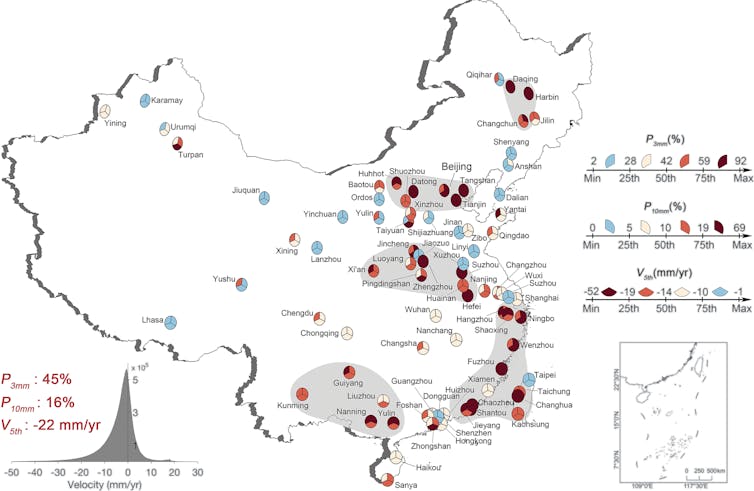

The authors analysed satellite-derived data from 2015 to 2022 across China’s 82 most important cities to produce accurate and consistent maps of vertical land movement. Consistently measuring subsidence in all these cities, with a collective population of nearly 700 million people, is a great achievement.

They found 37 of the 82 cities they looked at were sinking, and nearly 70 million people are experiencing rapid subsidence of 10mm a year or more. This may not sound much but the subsidence accumulates over time and can damage infrastructure and buildings, and make floods more dangerous.

Where China’s sinking cities are found:

There are a number of sinking hotspots in China mainly in the east of the country, especially near the coast. These include the inland capital Beijing and the nearby (London-sized) port city of Tianjin.

Why cities sink

The subsidence has multiple causes, both natural and human-induced. Most large changes are human-induced. For cities built on geologically young sediments such as river deltas and floodplains, the biggest cause of subsidence is people withdrawing or draining water found underground.

This groundwater is safer to drink than surface water, so as a city grows it tends to extract even more water from below. This causes the soil to consolidate and the surface above to lower.

Other causes of city sinking include mines below some cities slowly collapsing, or land reclamations which are widespread along China’s coast. The weight of the fill used to reclaim new land from the sea can cause the land to sink.

Cities often sink unevenly, and this differential subsidence is a much greater challenge than when an entire city sinks at a uniform rate. For instance traffic vibration and tunnelling is also a contributing factor in certain areas – the new study found that Beijing is sinking much faster near subways and highways, up to 45mm a year.

Subsidence is often attributed to the weight of buildings, but this is probably overstated as modern foundation design aims to minimise the effect to avoid building damage.

Coastal cities such as Tianjin are especially affected as sinking land reinforces the problem of climate change-driven sea-level rise. The sinking of sea defences is one reason why Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005.

China’s biggest city Shanghai has subsided up to three metres over the last 100 years. Built on already low-lying land where the Yangtze Delta meets the ocean, much of the city is barely above sea level, greatly increasing the consequences if flooding occurs.

The authors of the new study combined rates of subsidence with projected sea-level rise to estimate that the urban area in China below sea level could triple in size by 2120, affecting between 55 million and 128 million residents. This could be catastrophic without massive adaptation.

How to stop sinking

Parts of Japan’s two largest cities, Tokyo and Osaka, sank by several metres during the 20th century. However, in the 1960s and 70s both banned groundwater withdrawal and provided alternative surface water supplies. This in turn stopped or greatly reduced city subsidence – the strategy had been effective.

Shanghai in China followed a similar strategy a decade or so later. The latest study noted the city today has relatively moderate subsidence compared to the hotspot of Tianjin. The Chinese government already aspires to mitigate human-induced subsidence, and this new study shows all the cities where this needs to be considered.

But if cities are unable to stop or control sinking then they have to adapt to the reality, especially in coastal areas. In China’s low-lying coastal areas, dikes are almost universal. But a combination of sinking land and rising seas means they are already being raised.

As illustrated by the new China study, satellites are delivering unprecedented subsidence data in time and space. They provide consistent measurements across China (and potentially the world) and overcome concerns about sinking equipment which make subsidence so difficult to measure on the ground.

These satellite measurements can be repeated regularly to identify trends, and provide an important step on the road towards a solution to sinking cities. As someone who started their career when ground surveying was the norm, this is all very exciting.

Robert James Nicholls, Professor of Climate Adaptation, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.