Toby James, University of East Anglia and Holly Ann Garnett, Royal Military College of Canada

This year has been widely proclaimed to be the year of elections, with national elections expected in at least 64 countries. This means that half of the world’s population will have the opportunity to change their government, choose their representatives and indirectly shape policy. It began as a year of hope – and the prospect of democratic empowerment.

But so far in 2024, elections have already been marred by problems. February elections in Pakistan were riddled with allegations of rigging and irregularities.

Polls were opened in Belarus, but were labelled as a “farce” by opposition parties, most of which were banned from the ballot paper. International observers have called out crackdowns on human rights defenders and activists who have been “imprisoned in deplorable conditions, without the right to a fair trial”.

Meanwhile, voters are heading to the polls in Russia, where all meaningful opposition was effectively stifled before election day. The results were declared by many as a foregone conclusion before the ballots are counted.

Threats to elections such as disinformation, inadequate funding of electoral authorities, a lack of transparency over political donations and restrictive voter identification requirements have been flagged as concerns elsewhere in the world where elections are due to happen – including the UK.

Summit for Democracy

This should come as no surprise. The reality and wider narrative in 2024 has been that we live in an era of “democratic backsliding”. According to a recent report from the V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, entitled The Varieties of Democracy, the global level of democracy in 2023 was back to that in 1985 – before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Autocracy has been growing in eastern Europe and south and central Asia. There are also signs of democratic decline even in the older democracies such as the UK and USA.

In response to these broad international developments, the US president, Joe Biden, launched the Summit for Democracy in December 2021, claiming that the defence of democracy was “the defining challenge of our time”.

Political leaders were asked to make commitments to improve democracy in their own backyard. More than 100 governments made written and video commitments for how they would do this. The first summit was virtual because of the pandemic, but this year, leaders are flying to Seoul, South Korea, for the third Summit to discuss how to improve the quality of democracy and elections in their countries.

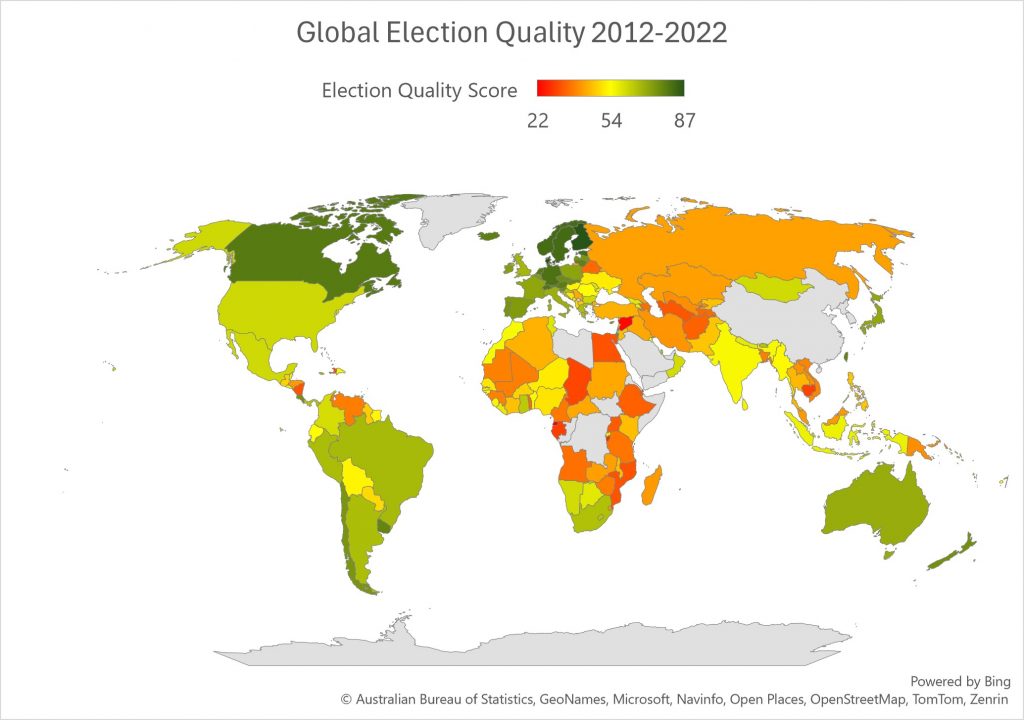

There is considerable work to be done to improve elections globally. Since 2012, the Electoral Integrity Project, an international academic think tank which researches how to improve elections, has published data on election quality. The map below shows the average election quality between 2012-2022, using this data. Countries in green have the highest quality, while those in red have a lot of work to do to improve election quality.

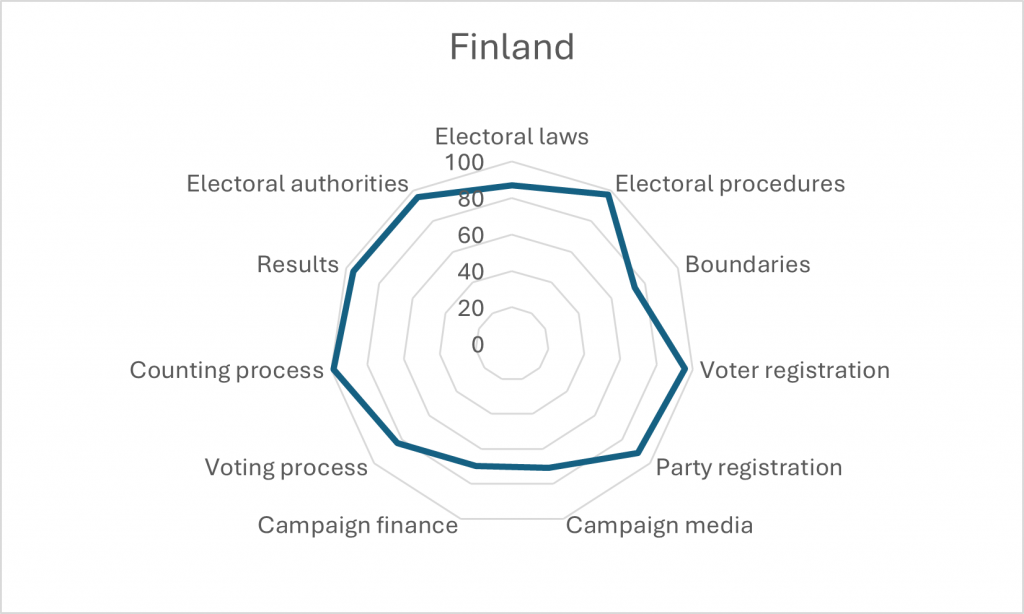

Election quality is the highest in Finland (see graphic) where electoral laws are fair to smaller parties, voter registration is seamless and electoral authorities are professional.

Across the border in Russia, where – as we’ve heard – voters are headed to the polls, the government has almost complete control of the broadcast media which slavishly toes the government line, election results lack transparency, most prominent opposition candidates are banned from the ballot – or are either in prison, exiled, or – as in the case of Alexey Navalny – have died in mysterious circumstances.

But even in Finland there are areas for improvement. There is scope for better transparency in how election campaigns are funded and equal access to campaign funds.

Finland is not alone – money is the biggest threat to elections. Campaign finance is weakest aspect of elections around the world according to our data. The idea that underpins democracy is that everyone has an equal chance at the ballot box. So finding a way to stop the flows of money that give some candidates and parties an unfair advantage remains a central problem.

Commitments missing the mark

Leaders have been reluctant to use previous summits as an opportunity to make commitments to improve their elections. So far in the first two summits, only 19 countries have committed to improving the quality of their elections.

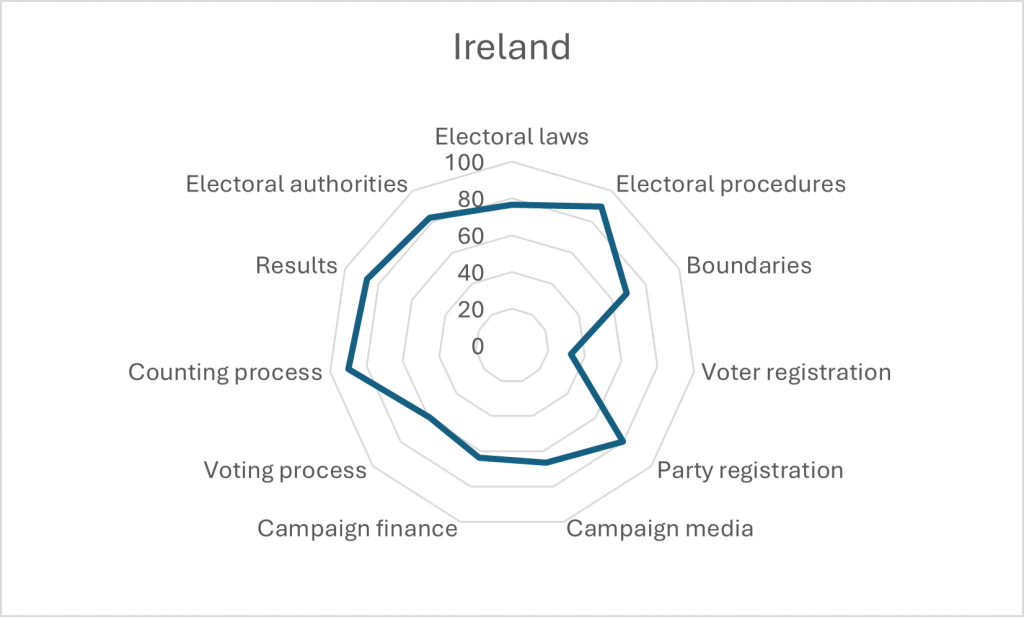

But some leaders have set examples by making pledges to improve the integrity of their country’s elections. In 2021, Ireland set out an extensive range of commitments, some of which are now a reality. This included setting up an independent electoral commission at a time where the independence of electoral authorities has been claimed to be under pressure in countries including the UK and Mexico.

Moreover, Ireland has been addressing weaknesses in its electoral processes. As the graphic above shows, Ireland’s greatest weakness elections is its voter registration process – and the Electoral Reform Act of 2022 has set in train a process for modernising this.

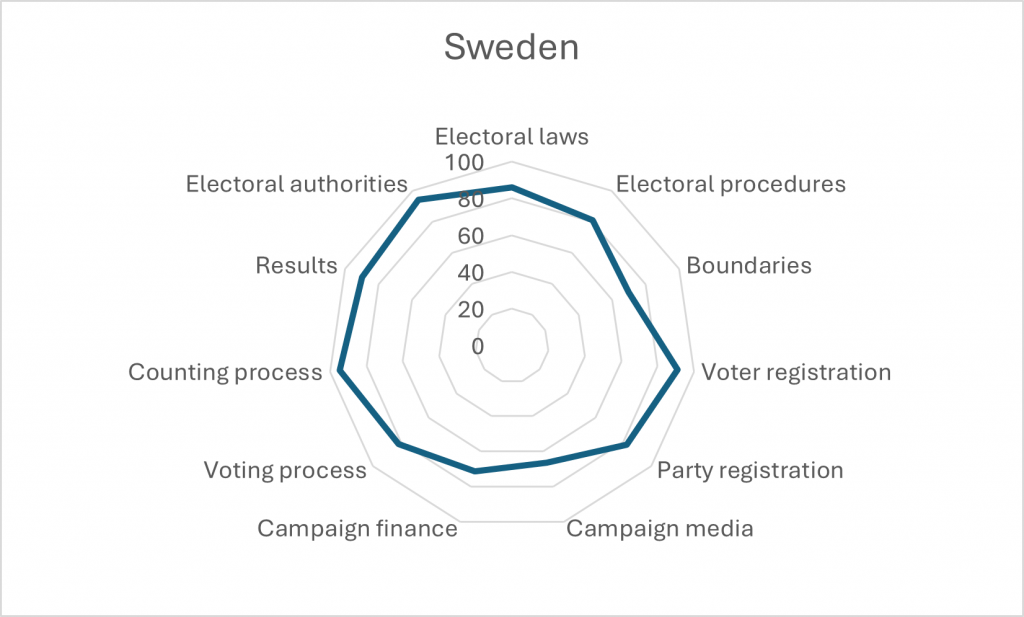

The medicine being prescribed by some governments, does not fit the problem, however. Sweden’s elections are thought to be among the fairest in the world. The country made a commitment in 2021 to improve voter turnout. But according to the Electoral Integrity Project data, the most important areas for improvement are party donations and transparency.

Most worryingly, most countries have made no promises to improve elections at all. Free and fair elections are an indispensable part of democracy. This year, as half the world votes, successful leaders need to commit to work with all partners across the political spectrum and civil society to make elections fairer in the future based on the evidence.

So the 2024 Summit for Democracy is an opportunity for world leaders to make concrete commitments to ensure that elections really are a moment of free expression and empowerment – rather than autocratisation, control and disempowerment. They should do this through the use of evidence and collaboration.

Toby James, Professor of Politics and Public Policy, University of East Anglia and Holly Ann Garnett, Class of 1965 Professor of Leadership, Royal Military College of Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.