After Israel’s third election in a year in early March, parties opposing Benjamin Netanyahu – the Israeli prime minister known as Bibi – secured a small majority in parliament. In a blow to Netanyahu, on March 15 these parties informed the Israeli president, Reuven Rivlin, that his rival Benny Gantz – the leader of the Blue and White list, a big tent political alliance – should be given the mandate to form a government. Gantz now has up to six weeks to complete this task.

In addition to losing his Likud party’s parliamentary majority, Netanyahu is due to go to trial in May for alleged corruption, facing charges including breach of trust, accepting bribes and fraud. And yet, it’s not clear whether the Netanyahu era is over, as the anti-Netanyahu majority in Israel’s parliament is fractured.

Gantz’s political positions on many of the big issues have remained rather vague, but he has taken a strong stance against government corruption and in favour of prime ministerial term limits.

To form a government, he will need the support of the remains of the Labor coalition and of the Yisrael Beiteinu (Israel Our Home) list. That is the (relatively) easy part. The more complicated part of forming a coalition will be how to deal with the Joint List, an alliance of Arab-majority political parties which has emerged as a serious electoral force.

Gantz will need to secure support from the Joint List to form a working coalition in parliament, and at the same time, make sure the more hawkish members of his own party do not jump ship. Whether he can or not has long-term consequences for Israeli democracy.

Down a slippery slope

Israel has undergone some significant legal changes under the rule of right-wing governments since 2015. A controversial Nation-State Bill adopted in July 2019 highlighted Israel’s Jewish identity, while ignoring fundamental democratic and equality principles.

Other bills that would weaken the judiciary have been proposed by legislators who support Netanyahu, including the “override clause” that would enable parliament to bypass the High Court. There have also been attempts to politicise the media. One of the court cases against Netanyahu involves his alleged offer of lucrative deals to media tycoons in exchange for favourable coverage.

Over the course of the past year, Netanyahu’s party has also negotiated various pacts with Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power) a far-right overtly racist party, in an attempt to secure a right-wing majority. During the 2019 and 2020 election campaigns, Netanyahu and his partners used harsh and inflammatory language against Arabs. The underlying goal of these statements was to question the loyalty of Arab citizens to the Israeli state, and the legitimacy of their political participation.

These actions matter. Research conducted in the US shows that when leaders use inflammatory language, citizens who hold prejudiced views are more likely to express and act upon their prejudices. Another study looking at 17 European countries found that the presence of far-right parties in parliament can cause voters on both sides of the political divide to move further to the extremes.

With attacks on the elite and references to the “will of the people”, Netanyahu is practising textbook populism. This is a direct threat to Israeli democracy.

Threats to democracy

There are two main groups among the world’s democratic regimes. The first is liberal democracies, characterised by protections of individual and political liberties, the rule of law, judicial and legislative oversight of the executive, and of course: free and fair elections.

The second, the group of electoral democracies, also generally have open and competitive elections and guarantee reasonable freedoms of association and expression. However, in contrast to liberal democracies, they fall short when it comes to protection of individual liberties, the rule of law and oversight of the executive.

Scholars at the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem) – a democracy studies centre that I was involved with – concluded in 2018 that Israel had moved into a grey zone between electoral and liberal democracy.

V-Dem’s data can help shed light on the trajectory of democracy in Israel. The data is collected by administrating thousands of detailed surveys to experts from across the world, asking them to provide scores on various aspects of democracy.

Democracy holding up, for now

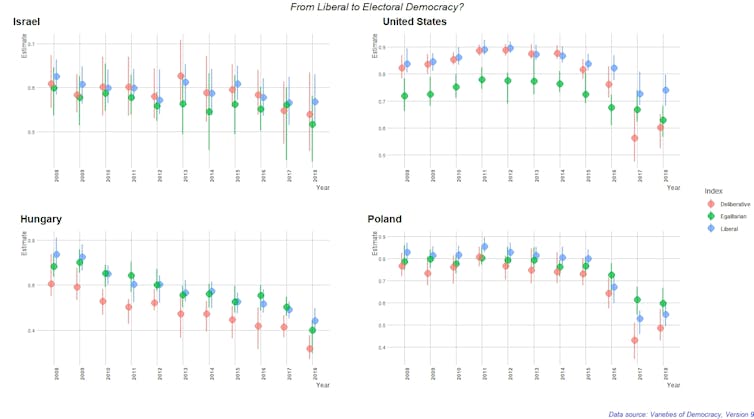

The graphs below present trends in three key aspects of democracy: the deliberative (the degree to which political decisions are based on respectful dialogue), egalitarian (whether members of all groups are able to participate and exercise their rights) and liberal dimensions. Broadly speaking, higher values indicate a more liberal democratic regime. Alongside the US and Israel, also included are Poland and Hungary: two other countries that have moved into electoral democracy territory from liberal democracy.

The graphs show that overall, Israel experienced a much slower decline in its level of democracy compared to other countries in which liberal democracy has been challenged – at least up until 2018. If we incorporate the statistical uncertainty, captured by the vertical lines on each side of the dots in the graph, we can see that experts are quite uncertain as to whether there has been a decline at all.

Still, there is a caveat: since the data covers the period up to 2018, it doesn’t take into account the recent developments in Israel, including the recent electoral campaigns.

At least in terms of the time period, perhaps most comparable to Israel is the Polish case, where the right-wing Law and Justice party took over in 2015, the same year Netanyahu formed his first genuine right-wing coalition. Although the data indicate that in 2018, the two countries were similar in terms of their overall level of democracy, the Polish decline has been much sharper. Meanwhile, Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has drifted further into electoral democracy in the nine years since he took office. And the data for the US is most alarming for proponents of liberal democracy.

This research could indicate that despite the attacks by Bibi and his allies, democratic norms and institutions in Israel have proven to be resilient. Still, based on recent events in Israel and trends in other countries, supporters of liberal democracy should hope that the forces opposing Netanyahu-style politics will be able to overcome their differences and form a government.

If they fail and Bibi stays in power, there will be more attacks on democratic institution and norms. It may not be the end of democracy in Israel, but it will most likely lead to hollower version of it.

Dr. Eitan Tzelgov is a Lecturer in Politics (Quantitative Methods) at the University of East Anglia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.