Margaret Thatcher’s archives have proved to be a surprising source of insight into the relationship between politics and popular culture, argues John Street.

Last year saw the release of the No. 10 briefing that she received for her interview with the pop magazine Smash Hits. ‘You may not enjoy the interview’, she was told, but she was reminded that ‘The way you handled the [Saturday] ‘Superstore’ appearance is still the subject of praise from youngsters.’ She was encouraged to tell her interviewer that Tories weren’t responsible for Johnny Rotten. ‘The most extreme form of “pop” rebellion,’ her brief noted, ‘was the punk phenomenon and this happened during the last Labour government.’ Her government could boast instead that ‘music from the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical “Phantom of the Opera” continues to do well in the charts.’

Last year saw the release of the No. 10 briefing that she received for her interview with the pop magazine Smash Hits. ‘You may not enjoy the interview’, she was told, but she was reminded that ‘The way you handled the [Saturday] ‘Superstore’ appearance is still the subject of praise from youngsters.’ She was encouraged to tell her interviewer that Tories weren’t responsible for Johnny Rotten. ‘The most extreme form of “pop” rebellion,’ her brief noted, ‘was the punk phenomenon and this happened during the last Labour government.’ Her government could boast instead that ‘music from the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical “Phantom of the Opera” continues to do well in the charts.’

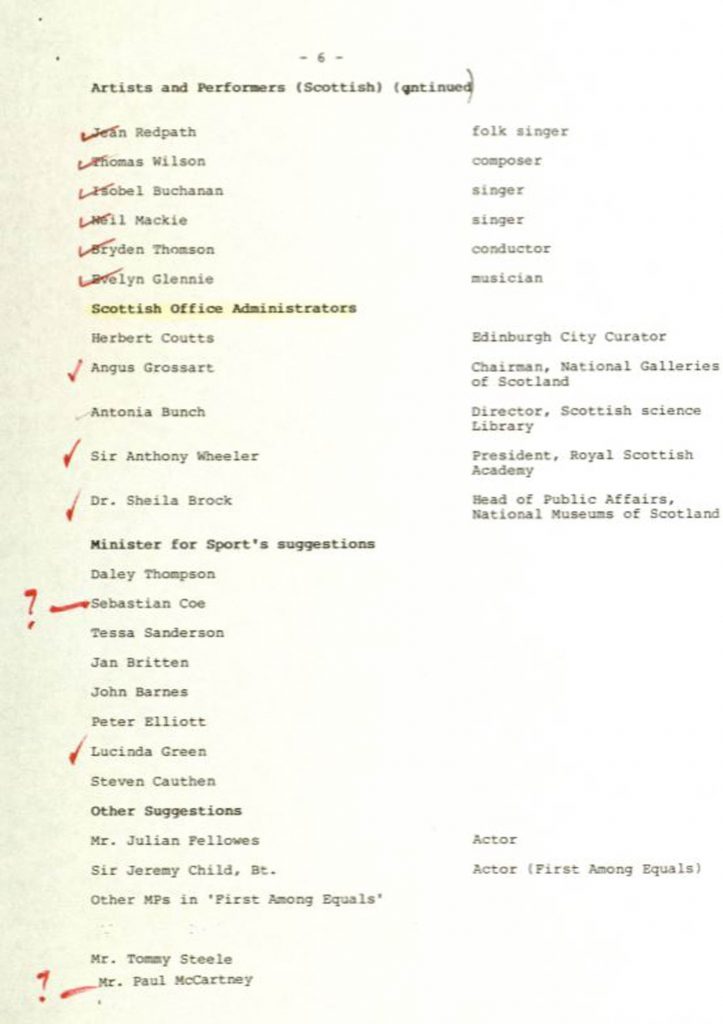

This week we have seen the recent revelations of her husband’s vetting of the guest list for a celebrity party at Downing Street. Just as the Smash Hits briefing was revealing of the anxieties and attitudes of the Conservative government about its image, so too does Denis’s judgement on the showbiz invitees.

There are the obvious political judgements. Denis’s accompanying memo notes: ‘I accept, of course, that not everyone who comes to our Receptions are necessarily on “our” side.’ Hence, the three ticks of welcome bestowed on the notoriously reactionary golf commentator Peter Allis, who was only outdone by the four ticks given to comedian Eric Sykes. Those also blessed with ticks – albeit a more restrained two – were Tim Rice, Judith Chalmers, Ronnie Corbett, Penelope Keith and Donald Sinden. All, in their different ways, representative of a middle-class, conservative England.

Such judgements might well be seen to represent the political sympathies of the individuals (insofar as we know about them), but the conservatism also applied to the cultural forms with which they were associated – situation comedies, mainstream musicals, BBC Radio 2….. It is perhaps no surprise that Gilbert and George are accorded two question marks (one for their art, the other for their sexuality?)

Such judgements might well be seen to represent the political sympathies of the individuals (insofar as we know about them), but the conservatism also applied to the cultural forms with which they were associated – situation comedies, mainstream musicals, BBC Radio 2….. It is perhaps no surprise that Gilbert and George are accorded two question marks (one for their art, the other for their sexuality?)

Denis was reluctant to host ‘those who publicly insult the PM.’ Hence, according to the press coverage, the question marks against Paul McCartney. Hence too the general ban on BBC executives, and the question mark against newsreader Jan Leeming (and possibly Janet Brown, who imitated Mrs T on television). But why did Shirley Bassey and Paul Daniels also get singled out? Too populist?

Whatever the answer, the list of potential guests offers a more general insights into the relationship between the established political order – as it was in the 1980s – and popular culture. First, there are many names that receive neither a tick nor a question mark, suggesting that Denis was unsure as to who they were. Sportspeople (typically men) are almost all ticked (although Seb Coe gets a question mark), but artists, dress designers, theatre actors and authors pass by unmarked. These are worlds fall outside that the Thatchers inhabited. Overall though, the list and the emendations are suggestive – as is the Smash Hits briefing – of how politicians were increasingly seeking to the link themselves with showbiz. And Denis’s response to those names is indicative of how the link between politics and popular culture extends beyond the individuals and their political sympathies into the personas and performances with which they are associated.

John Street is professor of politics at the University of East Anglia