Shortly after the Nice terror attack in July, Kelvin MacKenzie, a former editor of The Sun newspaper addressed the issue in his regular column in the tabloid newspaper: “Was it appropriate for [Fatima Manji] to be on camera when there had been yet another shocking slaughter by a Muslim?” he asked.

His comments related to Channel 4 News’ decision to field a “young lady wearing a hijab”- as MacKenzie described her- to anchor its evening news bulletin the night after the attack.

In MacKenzie’s opinion, this decision was “massively provocative”. An alternative opinion is that it was a socially responsible attempt to challenge negative stereotypes of Muslims at a time of heightened fears. Yet another is that it was simply a decision to field the best news presenter that Channel 4 News had available on the day.

But as well as expressing an opinion, did MacKenzie’s column violate the Editors’ Code of Practice? The Code is a set of rules that newspapers and magazines can voluntarily pledge to accept. It is written by the Editors’ Code of Practice Committee, made up of ten editors from the national, regional and magazine industry, as well as three lay members and the chairman of the Independent Press Standards Organisations (IPSO), the organisation which handles complaints under the Code.

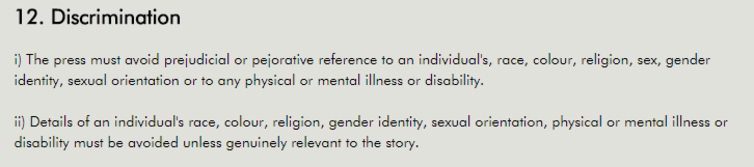

In July, Manji lodged a complaint with IPSO about MacKenzie’s column, claiming that it breached Clause 12 which relates to this discrimination:

IPSO has subsequently published its ruling on Manji v The Sun (No. 05935-16, September 29, 2016) saying that MacKenzie:

was entitled to express his view that, in the context of a terrorist act which had been carried out ostensibly in the name of Islam, it was inappropriate for a person wearing Islamic dress to present coverage of the story.

This ruling is perverse and incomprehensible: one is left wondering what IPSO thinks it would take to qualify as a violation of Clause 12.

Mealy-mouthed and toothless

Surely MacKenzie’s column qualifies as a “prejudicial” and “pejorative”- two of the terms that define IPSO’s Clause 12- reference to Fatima Manji’s religion. The reference to her religion was unmistakably implied by the reference to her wearing a hijab, the fact that Mackenzie was questioning whether Manji should have been reporting on ” another shocking slaughter by a Muslim”, and by his follow-up question: “Would the C4 editor have used a Hindu to report on the carnage at the Golden Temple of Amritsar?”

The Editors’ Code- and IPSO itself- are doubly toothless. The Code is voluntary and it is being applied by the regulator with a breathtakingly narrow interpretation of the key clauses.

What is more, the Code itself leaves untouched many other harmful forms of discriminatory language. Clause 12 defines discriminatory material in terms of whether it makes “prejudicial or pejorative” or ” [ir]relevant” reference to “an individual’s” protected status identity. The problem is that many forms of hate speech- and indeed, many of the evils of hate speech, including a climate of hatred, feelings of insecurity, damage to people’s sense of civic dignity or equal status and the silencing effect- operate at the group level.

IPSO’s record

Previous IPSO cases show that it is unlikely to find in favour of a complainant if the speech in question makes no reference to an individual or individuals. Thus, in Greer v The Sun (No. 02741-15, July 20, 2015) involving a complaint against Katie Hopkins’ infamous article in The Sun published on April 17, 2015, in which she compared refugees to “cockroaches” and advocated the use of gunships to prevent their entering Europe, IPSO ruled that the article did not breach clause 12 because it mentioned an entire group or category of people.

In another case, IPSO tied itself up in knots trying to apply Clause 12 to a case involving a group of individuals. In Partnerships in Care v Ayrshire Post in July 2015, IPSO ruled that Clause 12 could be engaged where a reference is made to “a distinct class of individuals”. In this case, the newspaper used the term “deranged criminals” to refer to residents of Ayr Clinic, a secure psychiatric unit.

Perhaps IPSO reasoned that a reader could, using information in the public domain, find out the identity of the “distinct group” of residents. But at the same time, IPSO inexplicably rejected the complaint under Clause 12 maintaining that the term “deranged” had been used “with reference to those individuals’ criminal behaviour; it was not therefore discriminatory in relation to their mental health specifically”.

It is interesting to consider how IPSO would handle a complaint made about the publication of negative stereotypes about people from Liverpool or from Scotland. What if a reader could, using the electoral roll, find out the identity of individuals living in these parts of the country?

New protection needed

I have written to the Editors’ Code of Practice Committee suggesting a better alternative. That they immediately bolster Clause 12 with the following additional sub-clause

iii) The press must also avoid publishing material that is comprised entirely and overwhelmingly of negative stereotypes or stigmatisation of a group identified on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation or any physical or mental illness or disability.

I believe that the new sub-clause would both provide greater protection for groups against hate speech material that does not name specific individuals, but would at the same time be drawn narrowly enough to prevent excessive restriction of free speech on issues of public interest relating to groups, It would also bring the Code into line with similar regulations adopted by media organisations in other parts of the developed world.

This post originally featured on The Conversation.com

Dr Alex Brown is Senior Lecturer in Contemporary Social and Political theory at the University of East Anglia

Image Credit: Flickr