In the light of recent celebrity interventions into the Scottish independence question, Dr Alexandria Innes considers her own own position and urges caution against the construction of new barriers.

Everyone from David Bowie to Noam Chomsky to J.K. Rowling is weighing in on votes for Scottish Independence, not least my pro-independence Scottish father and my anti-border Cypriot mother who have called me on a few occasions mid-discussion to say ‘Andri, what do you think?’ After three phone calls of that type within about a fortnight, I started to ask myself, what do I think? The question of Scottish independence is one I find very difficult to answer. As my parents cannot agree and I am undoubtedly the product of both of them, I face an internal conflict.

My personal background bears heavily on the question. My father is Scottish but has lived almost all his life in England – in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (so, you know, close to Scotland). He was born in Fraserburgh and is very proud to be Scottish. He owns an Innes tartan kilt with all the trimmings. When my American in-laws visited the UK for the first time he insisted on wearing the full regalia and serving them haggis for dinner, followed by cranachan and whiskey from a Quaich that we passed around the table. Being American, the in-laws thought it both quirky and delightful.

My mother, on the other hand, while also living her whole life in Newcastle, is Cypriot by origin. Consequently, she is suspicious of any type of partition or wall given that Cyprus remains divided – Nicosia is the only divided capital city in the world. Scottish independence from this perspective means division, means creating a new border, a new set of differentiations and exclusions, a new process of Othering.

I have spent the last decade or so studying international relations, specifically the politics of migration. I’ve also had a keen interest in the Cyprus conflict since being a child – waking up to the sound of sirens at 4am on the 20th of July each year will do that to you. I was taken to see the wall in Nicosia when I was probably about 10 years old. I saw this live on television in 1996 – a Greek Cypriot taking part in a demonstration was shot as he attempted to change a Turkish flag for a Cypriot one in the UN Buffer Zone in Cyprus (apologies for politically charged captioning on the video – I want to emphasise that the bordering of Cyprus inflicts violence on the island as a whole and on both sides of the conflict). I’ve been ardently against borders because of the violence they impose, which I’ve witnessed both in my personal life as a (part) Cypriot and in my research which has been ethnographic and embedded in migrant communities. The idea of a new border, then, is repellent to me.

However, my Scottish side every once in a while pokes its head out and says ‘but… but… historic oppression! Land seizures! The highland clearances!’ The romantic ideal of independence is linked to nationalism, the right to self-determination, Braveheart! It’s hard to separate it from that. Idealistically and emotionally, then, Scottish independence is a great thing. In that regard the desire for independence is a protest against oppression. Scotland is another postcolonial state that wants the political dignity of self-determination.

Borders are inextricably linked to property rights. The right to own property is not an acquisitive right so much as it is an exclusive one. You get to take something and exclude others from access to it. Territorial borders are always about exclusion, are about ‘protecting’ those inside who deserve to be there from the clamouring masses ‘outside’ who want to take from them. But Scottish independence does not evoke such an assumption, it represents ‘taking back’ rather than ‘excluding’ and I think the privileges of the English over the Scottish are historically evident.

However, can the idea of ‘taking back’ be separated from exclusion? Can the drawing of a new border be a balm offering protection? I don’t think any border can be separated – truly separated – from violence, even without the physical manifestation of a wall. Even if a border is intended to right past wrongs we have to be cautious enough to consider what new wrongs might be made in the process. I am not against Scottish independence. But I do not think enough time has been spent considering what borders do. The globalised world might suggest that borders are less significant yet their significance is all too apparent for the people who want to cross them and are not allowed, who remain static and immobile in border towns, in detention centres, and in refugee camps around the world. If we buy into the desirability of a new border, then we reproduce the significance of borders. Is that something we want to do?

Alexandria Innes is Lecturer in International Relations at the University of East Anglia. Alexandria’s current research is at the intersection of human rights and security studies, focusing on how people who do not have citizenship or immigration status experience international relations. Her work has appeared in International Relations, Global Society and the Routledge Interventions series.

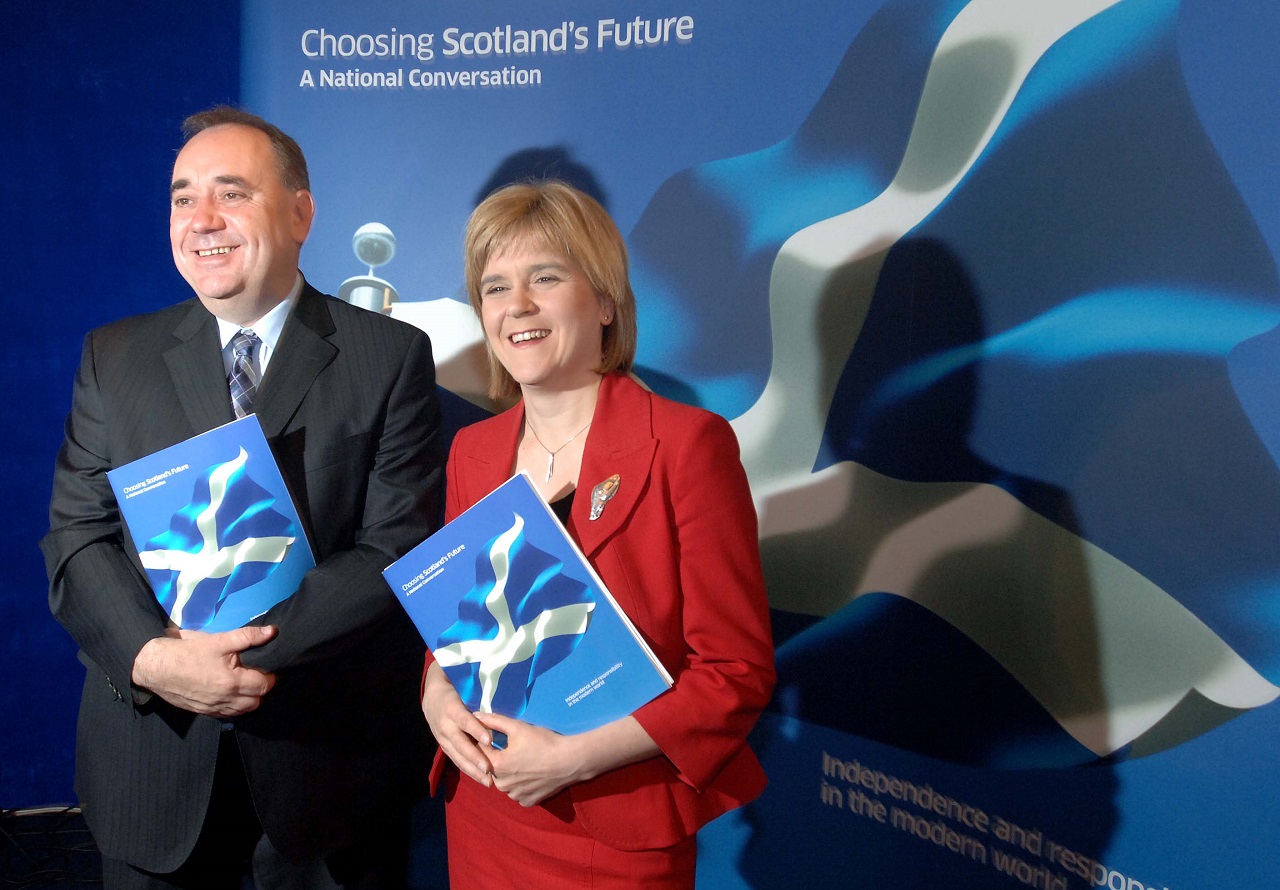

Photo credit: Wikipedia