Austerity and authoritarianism in Pakistan

by Juvaria Jafri (UEA)

In November 2024, demonstrators from various cities of Pakistan defied lockdowns to gather in Islamabad and demand that Imran Khan, former Prime Minister, be released immediately from jail. Khan, incarcerated since the summer of 2023, has been charged with a range of offenses, including corruption and immorality.

An excessively callous response from security agencies has quelled demonstrations for the time being, but the central issues raised have not been addressed. At first glance, the protestors’ demand seems simple: free Imran Khan and hold fresh elections. But the discontent has much more complex roots in the political economy of Pakistan and its heightened and recurring encounters with authoritarianism and austerity. Khan’s political party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) was elected to power in 2018. But in 2022—as the Covid-19 pandemic abated and Russia invaded Ukraine—the PTI was ousted from government through a strategy backed by the Pakistan military and ostensibly supported by the Biden administration. The involvement of the US has been the subject of deep anti-Western conspiracy theories, perhaps most systematically articulated in the debates around the cypher case. Since then, a coalition of parties have liaised with the military to oversee constitutional amendments that limit judicial independence, the rule of law, and human rights protections.

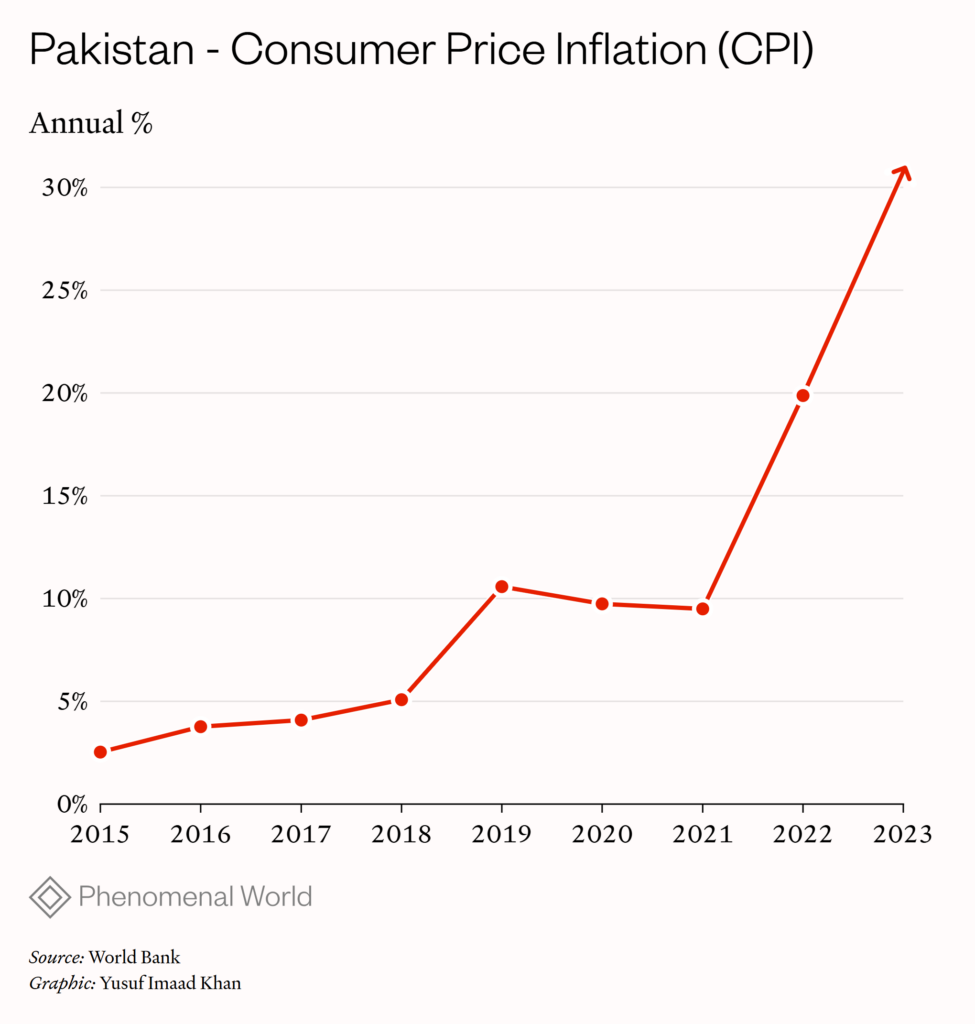

Khan’s own legacy is mixed. Even from a jail cell, he is an exceptionally powerful voice that condemns military overreach. But his own government had a reputation for curtailing democratic freedoms and for being complicit with the security forces in a regime of brutality and the violent repression of dissent. Nevertheless, his arrest last year has coincided with worsening cost of living pressures and the heightened presence of the military in politics. Tough economic conditions are underpinned by a tight monetary environment and high inflation. Young Pakistanis have been leaving the country and causing shortages in skills. To squelch unrest, the authorities have taken to blocking internet connectivity to limit access to platforms such as X, which might be used as tools for mobilizing protests. Internet shutdowns have been bad for business and unwelcome in a struggling economy.

Pakistan’s crippling and compounding economic struggles have a long and complex past, one that is closely intertwined with its position as a strategic geopolitical partner for the US in the region. This has complicated Pakistan’s relations with neighboring countries and exacerbated its structural position of dependence on foreign debt. While the rise of China as an alternative lender presents some opportunities for maneuver, Pakistan’s core social and political burden—its debt—remains.

Overlapping crises

Pakistan is among the most frequent users of IMF resources and has been under IMF-supported programs almost continuously since the late 1980s. For decades, Pakistan has continued to receive IMF loans despite failing to meet the lender’s stringent reform targets. From 1988 to 2000, the IMF agreed to loan Pakistan over $4 billion. But weak state capacity and the failure to meet conditionalities meant that only half of this sum—around $2.1 billion—was actually disbursed.

This dynamic—lending despite non-compliance—is not unique to Pakistan. It is a common feature of the IMF’s lending practices that arise from the institution’s dual role as both a lender of last resort and a vehicle for advancing the interests of powerful countries. The IMF’s programs, especially those imposed on Pakistan, proved unworkable because they entailed profuse tax burdens and unbearable price increases in staples like food and fuel. As a result, they regularly failed to achieve their stated goals, deepening the country’s economic instability and contributing to rising inequality. Moreover, the conditionalities attached to loans have been criticized for exacerbating poverty and undermining Pakistan’s development objectives. The IMF’s insistence on fiscal austerity and market liberalization has failed to address Pakistan’s fundamental structural issues, such as its low tax-to-GDP ratio, which severely limits the government’s ability to expand domestic fiscal space.

Beyond the hopeless cycle of lending and noncompliance, Pakistan’s economic vulnerability is also tied to the global financial system and particularly the dominance of the US dollar. Monetary hegemony, often referred to as the “original sin” of sovereign debt, restricts countries like Pakistan from borrowing in their own currency. As a result, they are forced to rely on foreign currency loans, exacerbating the risk of balance-of-payments crises, currency devaluation, and inflation. This creates yet another vicious cycle in which the demand for foreign currency to service debt exceeds the available supply, pushing countries further into economic precarity.

Pakistan’s reliance on external debt has consistently undermined its monetary sovereignty, complicating efforts to regulate the money supply and exchange rates effectively. The IMF’s stringent policies, which prioritize fiscal stability at the cost of domestic economic autonomy, often fail to take into account specific structural challenges. Because the debt burden grows every time the Pakistani rupee loses value, debt repayment invariably diverts resources from essential social services, such as healthcare, education, and basic infrastructure.

Structural challenges are compounded by a persistent paucity of US dollars. Pakistan has grappled with continuous dollar shortages throughout its history, a predicament deeply intertwined with chronic fiscal and trade deficits, as well as an overreliance on debt. When dollars are scarce, imports cannot be paid for, leading to shortages of food, fuel, and medicines, among other things. In such crisis situations, only external loans can come to the rescue. Despite various reforms, the root causes of these shortages remain embedded in both domestic and international financial structures.

One of the primary drivers of Pakistan’s dollar shortages is its chronic trade deficit. With the exception of three fiscal years (1947–48, 1950–51, and 1971) Pakistan’s exports have consistently lagged behind its imports. This imbalance has forced the country to depend heavily on foreign currency inflows, primarily through remittances, loans, and aid, to meet its external financing needs.

The structural issues underlying Pakistan’s trade deficit are multifaceted. Limited diversification of exports, reliance on low-value goods, and insufficient investment in value-added industries have constrained the country’s export potential. Meanwhile, a dependency on imported goods, including energy, machinery, and consumer products, exacerbates the deficit. Moreover, tax revenue collection has averaged just 10.3 percent of GDP over the last few decades—significantly below regional peers. In the fiscal year 2023–24, the equivalent of over 80 percent of tax revenue, according to the IMF, was absorbed by debt servicing.

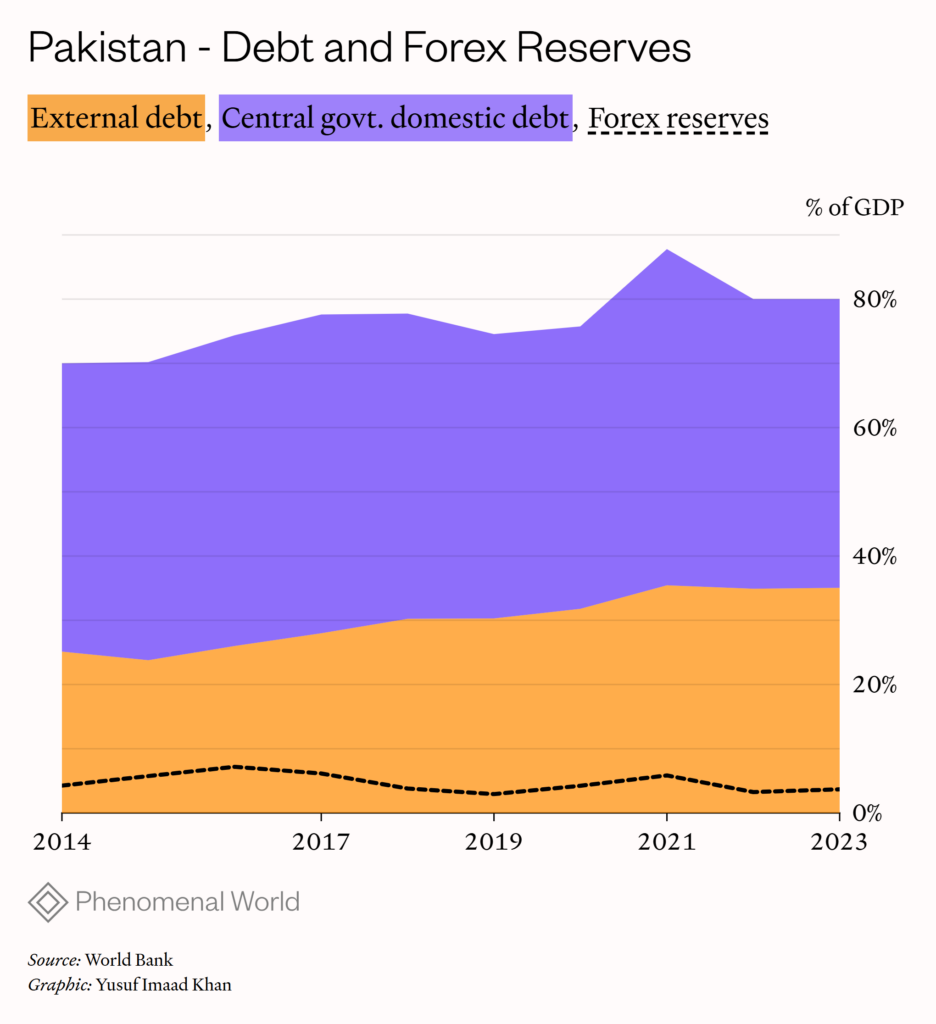

The heavy costs of debt, augmented by recurrent trade deficits and weak foreign exchange reserves are reflected in the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio. This stands at about 70 percent, with domestic debt accounting for about two thirds and external debt the rest. This crippling debt burden consumes resources that could have been used for more essential expenditures, such as on pensions, salaries, development projects, and subsidies. Consequently, Pakistan relies heavily on deficit financing, borrowing from both domestic and international sources, further exacerbating its debt challenges.

The rapid accumulation of public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt—in which the public sector reduces the risk for private sector lending—has created a “strong sovereign–financial sector nexus,” as described by the World Bank. Today, this sort of debt exceeds two thirds of Pakistan’s GDP. Most of this PPG debt is held by commercial banks in Pakistan and creates an interdependence between the government and the financial sector. Banks have tended to lend relatively little to the private sector because of an over-concentration of bank lending toward government needs. Currently, over 80 percent of bank lending is directed at the government, crowding out private sector investment and stifling economic growth.

Low revenue collection has been a major contributor to the fiscal deficit, regularly exceeding 5 percent of GDP in recent years. This trend violates the Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation Act or FRDLA, a critical fiscal rule meant to ensure prudent financial management. Compounding this issue is a flawed national fiscal architecture that has only worsened since 2010 when Pakistan implemented significant revenue-sharing reforms. These devolved financial powers to the provinces to empower local governments. But they introduced painful inefficiencies, including the duplication of tasks and fragmentation of responsibilities. As a result, the fiscal deficit has grown significantly since these changes were enacted.

These dynamics have worsened since the reversal of unconventional monetary policies. Quantitative easing led by the Federal Reserve and other large central banks, following the Global Financial Crisis 2007–9, created a low interest environment and boosted investor interest in the global South when banks had extra liquidity. But this was temporary. Over the last few years higher international interest rates have dramatically exacerbated Pakistan’s vulnerability to shocks. Managing its exchange rate, and meeting external debt obligations has become very challenging. Exchange rate depreciation has been a significant driver of Pakistan’s escalating public debt. Between 2012 and 2022, currency devaluation contributed 22.5 percentage points of GDP to the PPG debt level. Notably, 15 percentage points of this increase occurred during two periods of acute depreciation in 2019 and 2022. These revaluation losses far outweighed the reductions in debt stock achieved through favorable interest rate changes during the same period.

While interest rate changes contributed to debt accumulation prior to 2019, their impact was relatively smaller, accounting for an 11.4 percent GDP increase from 2012-2018. These figures highlight the critical role of exchange rate management in Pakistan’s fiscal stability. A weak currency not only inflates the cost of external debt servicing but also undermines investor confidence, exacerbating capital flight and further depleting foreign exchange reserves.

Geopolitics of debt

Pakistan’s chronic indebtedness and economic vulnerability is entangled with its Cold War history, when the country became a key US ally. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, Pakistan’s strategic location became pivotal in the struggle between the US and the USSR. This led to an influx of foreign aid, grants, and concessional loans (and also millions of refugees) as Pakistan was the base for the Saudi-American alliance behind the mujahideen, the coalition of anti-Soviet fighters that eventually defeated the Moscow backed government and took control of Kabul in 1992. The Taliban, which came to control most of Afghanistan by the mid 1990s, was formed because of infighting within the mujahideen coalition. The US once again enlisted Pakistan as a central partner when the Global War on Terror began in 2001. Pakistan again became awash with foreign currency; and through the Coalition Support Funds, the third largest recipient of the US military and economic support in the world.

Even before these events, Pakistan’s economy faced significant challenges. In 1971, Pakistan lost half of its territory when East Pakistan became the independent nation of Bangladesh. This moment of national upheaval coincided with a broader global shift that saw countries in the global South lose significant monetary power. Two pivotal events defined this era: the Nixon Shock and the oil shocks of the 1970s. The Nixon Shock marked the end of dollar-gold convertibility and laid the groundwork for capital account liberalization, allowing dollars alone to expand global credit. This shift restructured global finance and diminished the monetary autonomy of many developing nations, including Pakistan. Compounding these challenges, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) quadrupled crude oil prices, triggering a series of oil shocks that reverberated through economies reliant on imported oil.

The surge in oil revenues for producing nations found its way into global commercial banks as deposits, creating a surplus of funds that fueled a cascade of loans to countries in the global South. Pakistan, like many other nations, became a recipient of these petrodollar-driven loans, often offered with minimal scrutiny. The availability of cheap loans at negative real interest rates, owing to high domestic inflation, made borrowing an attractive option. However, this practice exposed Pakistan to significant exchange rate risks and constrained its ability to pursue independent monetary policies. Western banks, driven by the imperative to expand credit, were central to this recycling of petrodollars. The situation worsened later in the 1970s when rising interest rates made debt servicing prohibitively expensive, especially as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed structural adjustment conditions in exchange for financial assistance.

During this turbulent decade, Pakistan’s trade deficit became increasingly pronounced. The gap between imports and exports widened as the country struggled to bolster its export base. To bridge this gap, Pakistan turned to external lenders for assistance. However, the same period also brought some respite in the form of increased remittances from Pakistani workers in the Gulf states. Even today, the Gulf-South Asia migratory corridor is the largest in the world.

The oil boom in the Gulf significantly boosted worker remittances, which rose from 3.1 percent of GDP in 1976 to 7.7 percent in 1986, peaking at 10.2 percent in 1983—a historical high that remains unsurpassed. These remittances provided much-needed foreign currency inflows and played a critical role in mitigating the country’s current account deficit. Remittances continue to provide sustenance to Pakistan, often bringing in foreign currency inflows comparable to those earned from trade in goods. They have also acted as a hedge against oil price surges. When the Pakistani rupee (PKR) depreciates, remittances sent in foreign currencies such as US dollars, Saudi riyals, and UAE dirhams become more valuable in domestic terms, offering some relief to the economy. Despite these benefits, reliance on remittances has not compensated for the country’s failure to grow exports and rectify its trade imbalance.

The inability of Pakistani policymakers to address the structural issues in trade has deep political and economic roots. However, this domestic shortfall should not obscure the broader historical context that has shaped Pakistan’s economic struggles. The events of the 1970s stripped monetary power from the global South, leaving countries like Pakistan vulnerable to external shocks and dependent on subordinated financial arrangements. Some countries, particularly in East Asia, made themselves relatively secure by growing their foreign currency reserves through industrialization and export growth, but similar policies in Pakistan were not successful.

Geopolitics have been particularly detrimental for Pakistan’s regional trade. Pakistan’s three largest trading partners, in terms of two way trade, are China, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States. China shares a land border with Pakistan and is the only neighboring country to feature in the list of ten largest trading partners. Pakistan does some trade with Afghanistan, relatively less trade with Iran, and of neighboring countries, the least with India, despite sharing a border thousands of miles long. Afghanistan is impoverished from sanctions and from the US seizure of their central bank assets. Iran is today the most sanctioned country in the world after Russia. Bilateral trade ties with India have been particularly thin since the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution which had given Kashmir, a disputed territory, a special autonomous status.

New arrangements

In this context, the global rise of China has been alluring. The increasingly prolific lender has always been a strong ally to Pakistan. But China’s financial support for Pakistan—most notably through the multi-billion-dollar China–Pakistan Economic Corridor or CPEC—raises critical questions. Is China’s alternative model of development financing giving Pakistan the flexibility it needs to pursue its own policy goals? Or does reliance on another powerful lender simply shift, rather than undo, dependence?

The CPEC initiative has been hailed by many as a game-changer for Pakistan’s development, with promises of infrastructure modernization, energy security, and job creation. Yet, it also deepens the country’s financial ties to Beijing, adding layers of complexity to its already fraught economic landscape. China’s lending practices, characterized by long-term investments with fewer conditions, have been described as a form of “patient finance,” which contrasts sharply with the short-term, often disruptive loans provided by Western institutions like the IMF. This model of investment offers developing countries more room to maneuver, as it tends to be more tolerant of risk and less focused on immediate returns. Yet, while China’s financing approach offers a different dynamic, it is not without its challenges.

China’s massive financial footprint in Pakistan might be a welcome departure from IMF-imposed austerity measures, but it still raises concerns about the growing indebtedness. The narrative of “debt trap diplomacy” has been used—and also abused—to claim that China’s strategic lending could lead to Pakistan becoming economically beholden to Beijing. But this view oversimplifies the situation as it obscures the prominence of commercial creditors and private debt in Pakistan’s rising debt burden.

The internationalization of China’s currency, the renminbi, through mechanisms such as currency swaps, also presents an alternative to the dollar-based global financial system. China’s use of currency swap agreements with countries like Pakistan has provided a lifeline during periods of foreign exchange instability. This development reflects China’s broader ambitions to challenge the dominance of the US dollar in global trade, a goal that is also embodied in the creation of the “petro-yuan”—an attempt to internationalize the renminbi as a currency for oil trading.

The rise of China as a global creditor certainly marks a significant shift in the international financial system, but whether it can fully replace the IMF or offer a viable alternative to Western-dominated financial institutions remains an open question. There are also clear political limitations to any aspirations in which China replaces the IMF. These were revealed in efforts of the PTI government, particularly between 2018-9 to uphold election promises of avoiding IMF conditionalities, by seeking alternative sources of external finance. But the $ 15.8 billion gathered from different countries, including China, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates was not enough and Pakistan resumed negotiations with the IMF in the summer of 2019.

For Pakistan, the challenges of its political economy and turmoil that it produces cannot be separated from its indebtedness. This is inextricably linked to a global financial order, once again in the process of being reordered. Pakistan’s ability to navigate these new realities will determine the trajectory of its economic future.

Juvaria Jafri, Lecturer in International Relations, UEA

Juvaria is a Lecturer in International Relations at UEA and political economist with research expertise on the international political economy of the global South, particularly finance and development strategies, including fintech.

This article was originally published by Phenomenal World and is republished here courtesy of the editorial team. The original piece is available at: https://www.phenomenalworld.org/analysis/structural-dependence/

Image: PTI protests in favor of Imran Khan, 11 April 2022

Source: Voice of America https://www.urduvoa.com/a/pti-protests-in-cities/6523684.html