Alison Donnell, University of East Anglia

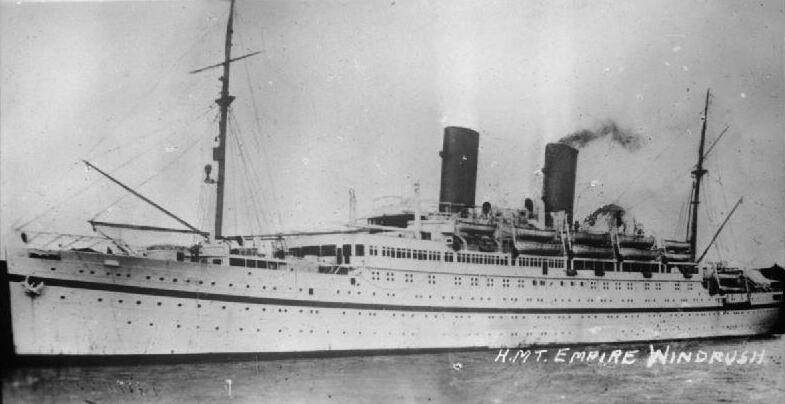

The 800 West Indians who walked down the gangway at Tilbury to make new lives in England in June 1948 had been encouraged to think of the country as their motherland. The literary contribution of the Windrush generation is just one example of how Caribbean-British people enriched the nation, but it offers an important opportunity to witness the transformative moment when empire came home, changing stories of Britain forever.

With their colonial education, these British subjects were already familiar with Big Ben and Buckingham Palace, and could likely have recited poems by Wordsworth, Shelley or Keats. Many were returning servicemen whose valiant contribution to the war effort had given them a strong affiliation with Britain as a land of freedom fighters. They were keen to contribute to the progressive reconstruction of their post-war homeland.

When Pathé News handed the microphone to Lord Kitchener, the suave young Trinidadian calypsonian, his homecoming serenade, London is the Place for Me, began a post-war tradition of Caribbean-British voices confidently bringing a new style and substance to expressions of belonging and nationality.

Given what we now know about the ongoing hostility towards the legal and personal claims of West Indians on Britishness, it is perhaps no surprise that the stories told around what became known as the “Windrush generation” were conflicted from the start.

A new story of Britain

The Daily Worker ran the headline: “Five hundred pairs of willing hands”, and chronicled Windrush as a moment of greater national unity, with skilled British subjects sailing home to help rebuild the nation. But antagonistic voices were loudly raising fears around immigration.

Prime minister Clement Attlee tried to dismiss these with his view that “it will be shown that too much importance – too much publicity too – has been attached to the present argosy of Jamaicans”.

This article is part of our Windrush 75 series, which marks the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain. The stories in this series explore the history and impact of the hundreds of passengers who disembarked to help rebuild after the second world war.

In fact, Windrush, and what it has come to symbolise, has turned out to be a more and more defining moment in telling the story of Britain. Writings by and about the Windrush generation have been fundamental to revealing the realities of the British empire.

Black Britons had been part of the nation for centuries before 1948. But the post-war wave of migrants from the British Caribbean meant the colonial order through which labour, resources and profits were generated out of sight, by exploitation and violence, could no longer be concealed or denied.

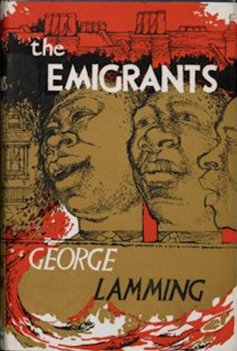

The incisiveness and originality of the insights Caribbean-British writers brought to questions of identity and belonging was recognised at the time. Writers like Wilson Harris, George Lamming, Roger Mais, Edgar Mittelholzer, V.S. Naipaul, Andrew Salkey and Samuel Selvon were reviewed in major newspapers.

Their writing rendered Caribbean people and places in ways that challenged traditional colonial views and gave descriptive power to the complicated realities of migrant lives. And just as they offered distinctive and compelling stories on what constituted Britishness, they also brought a new idea of literary English into circulation. The Caribbean language and episodic form of Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners are absolutely crucial to its poignant and pointed account of male migrant life in England.

Although women’s narratives of this time are only just being recovered, Beryl Gilroy’s 1976 Black Teacher and Joyce Gladwell’s 1969 Brown Face, Big Master are two memoirs that powerfully narrate the realities of Windrush women’s lives. They also reveal West Indian women’s experiences of migration, and their particular struggles for recognition in the colonising “motherland”.

Ongoing conflict

Most profoundly, Windrush writings across the generations have established that Britain needs to reckon with its colonial history and recognise all subjects in the extended nation made by empire. Yet when Guardian journalist Amelia Gentleman told the most significant Windrush story of our time, The Windrush Betrayal, Exposing the Hostile Environment, the persistent and brutal refusal of this reckoning became clear. https://www.youtube.com/embed/UK9m5RyCTPs?wmode=transparent&start=0

It is no surprise that Windrush history and literature are not included in the British school curriculum, but it is a regrettable omission. The huge success of Andrea Levy’s 2004 Windrush novel Small Island suggests the recognition of this moment as laying the foundations for what we know as post-colonial Britain. But it also makes clear that a celebration of what West Indians have contributed remains vital.

Yet Levy, in common with many literary descendants of the Windrush generation, has also written of the second generation’s experience of a hostile homeland. Her first novel Every Light in the House Burning, published in 1994, reveals the everyday realities of racism and the different perspectives between migrant parents and their British-born children.

Caryl Phillips’s brilliant debut novel The Final Passage also explores the pulls of migration and the strains for a young family settling in Britain from the Caribbean. These tensions gave tremendous creative energy to Linton Kwesi Johnson’s work, including the 1975 Dread Beat An’ Blood, which expressed the frustration and struggle of black youth against the hostile British establishment. https://www.youtube.com/embed/VOcsdC0WpV4?wmode=transparent&start=0

Perhaps the fact that Kitchener’s London is the Place for Me was revived as the anthem of the Paddington movies while the Windrush scandal was making headlines, speaks to the ongoing conflict. That is, between seeing Caribbean voices as central to Britain’s character as a convivial multicultural nation, and the real narrow nationalism of the conservative Britain we live in.

Ten great reads on the Windrush experience

1. Waiting in the Twilight Joan Riley’s 1987 novel offers a moving Windrush story of Adella, who spends the last day of her life in her Brixton sitting room “travelling back home” through her memories of Jamaica.

2. The Housing Lark Sam Selvon’s 1965 novel tells the story of a group of friends who come together to buy a house with Selvon’s characteristic blend of humour, tenderness and truth-telling.

3. Connecting Medium Dorothea Smartt’s stunning collection of poetry from 2001 explores the connections between the Caribbean and Britain.

4. Familiar Stranger: A Life between Two Islands The posthumous memoir of Stuart Hall, published in 2018, tells a highly personal story of the life between Jamaica and Britain that animated his brilliant insights into diaspora identities and post-colonial Britain.

5. Mr Loverman Bernadine Evaristo’s 2013 novel narrates a queer Windrush story and a poignant tale of belonging to Britain that unfolds in later life for her protagonists, Barrington and Morris.

6. Homecoming: Voices of the Windrush Generation Colin Grant’s 2020 publication offers an extraordinarily detailed and diverse portrait of the Windrush generation through oral histories.

7. Beyond Windrush: Rethinking Postwar Anglophone Caribbean Literature Edited by J. Dillon Brown and Leah Reade Rosenberg, this is an unmissable read for those interested in knowing more about the literary history of this period.

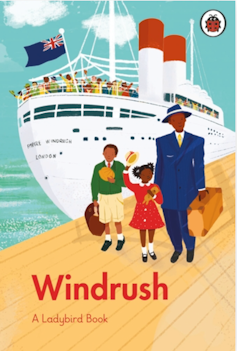

8. A Ladybird Book: Windrush Colin Grant, Emma Dyer and illustrator Melleny Taylor’s book is a recent addition to this favourite series and a fabulous way to introduce the Windrush story to young children.

9. A Place for Me: Stories About the Windrush Generation Published in 2021, this collection draws on materials from the Black Cultural Archives to tell 12 stories inspired by real people of the Windrush generation.

10. The Cambridge History of Black and Asian British Writing Edited by Susheila Nasta and Mark U. Stein, this offers a brilliant historical and critical context for appreciating Windrush writings.

Alison Donnell, Professor of Modern Literatures in English, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Image credit: wikipedia