The government’s rhetoric surrounding its plans to prevent asylum seekers crossing the Channel suggest their implementation will be simple. Yet Matilde Rosina and Oula Kadhum identify several important challenges that will have to be overcome first and assess the broader impact and human cost of pushing forward unworkable proposals for the sake of scoring political points at home.

On 7 March 2023, British Home Secretary Suella Braverman announced a new “Illegal Immigration Bill”. Aiming to stop migrants from arriving to the UK in small boats, the bill creates a legal duty to remove all migrants arriving irregularly on British territory and bans them from applying for asylum there. It also suggests revoking the rights of victims of modern slavery and has been condemned for its cruelty and illegality under international law. The Home Secretary herself admitted that the bill “pushes the boundaries of international law”, and the bill will no doubt face legal challenges.

Beyond legal challenges however, how feasible is the plan? Can the UK return all migrants arriving by small boats? Our answer, in short, is most likely not. Three challenges stand in its way: the lack of return agreements, the stalling Rwanda plan, and the practical difficulties and costs involved in returning migrants. Ultimately, the new bill is part of a political game, which nonetheless has real-world consequences for migrants, as well as the narratives and perceptions surrounding refugees and migration more broadly.

Challenge 1: A lack of return agreements

To start with, for returns to take place, readmission agreements with countries of origin or transit need to be in place. And yet, these are lacking.

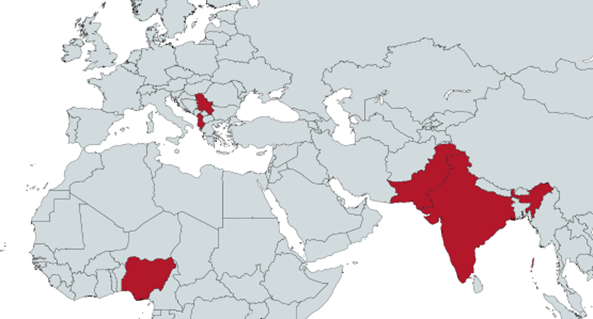

Agreements with countries of origin are few and often unfeasible. The UK has negotiated readmission agreements with Albania and India (2021), and Serbia, Nigeria and Pakistan (2022). While Albanian nationals made up the majority of those arriving in small boats in 2022, the other countries were Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq and Iran, with which the UK currently has no such return agreement. There is consequently a major discrepancy between the nationalities of arrivals and the countries the UK has return agreements with.

Moreover, it will be very difficult for the UK government to return Afghani, Syrian, Iraqi and Iranian migrants fleeing persecution, conflict or human rights abuses, due to the 1951 Refugee Convention. Indeed, in 2021, 11 people were forcibly returned to Iraq (against the 6,117 Iraqi who entered with small boats), and only 6 to Iran (against the 8,319 Iranian landings).

Deals with third countries are equally scarce. Pre-Brexit, the Dublin regulation ensured the UK could send asylum seekers back to EU states of transit. Post-Brexit however, due to the lack of negotiation of a returns agreements with the EU, this is no longer the case. Despite the recent deal to provide France with £478mn to support detention and surveillance, there is little evidence of EU member states being interested in signing a return agreement with the UK.

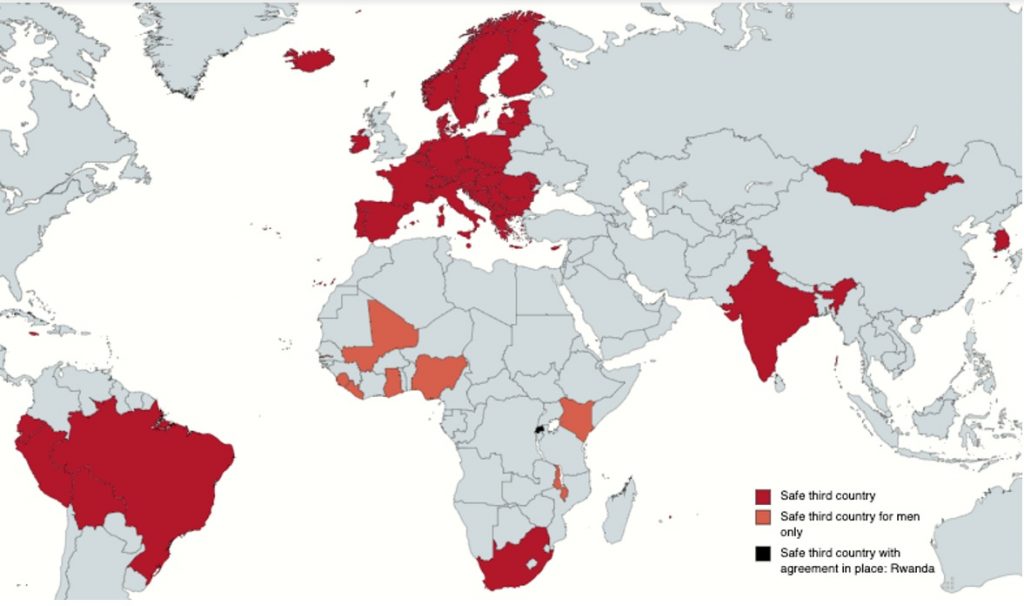

The new Bill identifies 57 “safe third countries” to which irregular entrants may be transferred (including all EU states). Of these 57 countries, the UK only has an agreement with one: Rwanda. Rwanda’s human rights record however, and the difficulties of the refugees already hosted there, make the label of “safe third country” questionable, before we even discuss the feasibility of such a plan.

Challenge 2: Failing Rwanda plan

The controversial Rwanda plan, originally proposed by the Johnson cabinet, foresees the transfer of asylum seekers to the African country to process their claims. Leaving aside the morality and legality of such a plan, its costs, negligible deterrence and counterproductive effects provide ample evidence of its lack of feasibility, but also its potential harm to UK national interests.

As of March 2023, no asylum seeker has been sent to Rwanda. A charter flight was supposed to leave on 14 June 2022, but was stopped at the eleventh hour. Since then, at least three airlines have withdrawn from the deal. The scheme is also very costly, as the UK is providing Rwanda with £120 million, and the charter flights used for removals reportedly cost an average of £165,000 per flight.

Even the Home Office’s Permanent Secretary, the department’s most senior civil servant, wrote in a 13 April 2022 letter to the previous Home Secretary Priti Patel that:

“[The Rwanda plan’s deterrent effect] is highly uncertain and cannot be quantified with sufficient certainty to provide me with the necessary level of assurance over [the policy’s] value for money.”.

Simply put, the Rwanda plan does not provide sufficient evidence that it will deter irregular migration, casting doubt on its cost-effectiveness.

Indeed, we know from scholarly studies that restrictive migration policies rarely act as deterrents and can often have inadvertent effects, which may come back and bite governments in ways they least expect. For example, the Rwanda plan might indeed lessen the burden of processing asylum claims in the UK, however these transactional forced migrations will only weaponise migrants further, and act as leverage for the Rwandan government in future negotiations with the UK.

The UN Refugee agency (UNHCR) has also deemed the Rwanda plan incompatible with the Refugee Convention. The deal is currently being challenged in court, and unlikely to be resolved this year.

Video Player

00:00

06:28

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi on the Rwanda plan: “This is all wrong”

Challenge 3: Practical difficulties of returns

Even when readmission agreements are in place, returns are no easy feat for any government, and are incredibly costly. The Home Office reported in 2013 that the average cost of a forced removal was £15,000. Adding to this, migrants entering Europe irregularly often lack passports, which makes identification procedures difficult.

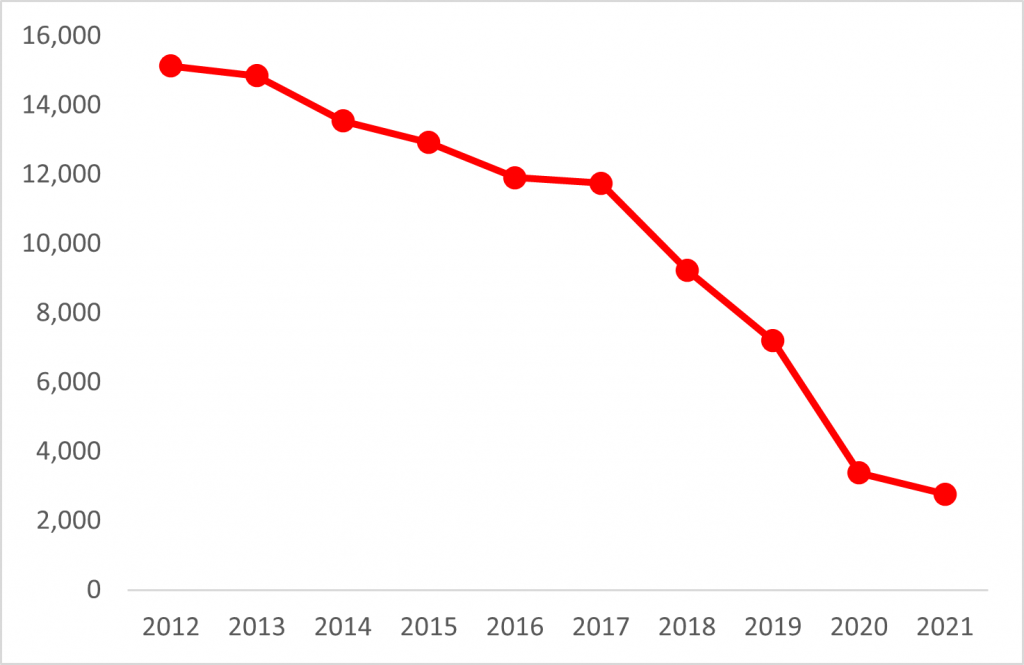

The challenge of returns is captured by Home Office statistics. Indeed, forced returns have consistently fallen over the last decade, from 15,134 in 2012 to 2,768 in 2021 (a decrease of 82 per cent). While this may be partly due to Covid restrictions, the trend long predates the pandemic, and is only likely to worsen in the post-Brexit era, due to the lack of a UK-EU returns agreement.

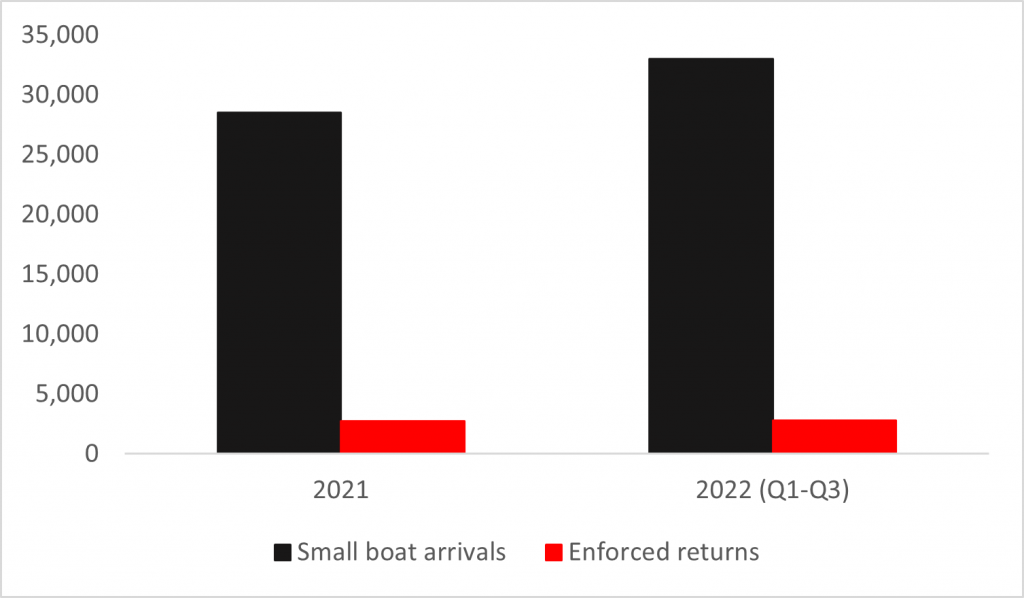

Moreover, less than 1 in 10 of those who enter with small boats are repatriated. In the first nine months of 2022, while 33,029 people entered the UK on small boats, the Home Office forcibly returned 2,805 people (8.5 per cent). Likewise in 2021, while 28,526 people arrived via small boats, 2,768 persons were returned forcibly (9.7 per cent). The fact that forced returns represent only a small proportion of small boat arrivals casts serious doubts on the government’s plans to remove all those entering irregularly.

Political games, real-world consequences

The strong rhetoric by the UK government on small boat arrivals and returns may be an attempt to take decisive action on irregular migration. Yet, the reality is that, unless the government creates safe and legal pathways for migrants and refugees to seek asylum, desperate people will continue to make desperate journeys on small boats to seek safety.

Choice of destination is often influenced by migrant networks and chain migrations, which have historically been shaped by colonial links and structural inequalities. So long as there is a disconnect between foreign policies and migration policies, and a failure to acknowledge why migrants are turning up in the UK, empty rhetoric is the only tool the government will have to address the “migrant crisis”, and many more people will be lost at sea.

So, while the Sunak government is certainly talking the talk on migration, evidence shows that it’s not walking the walk. Readmission agreements are lacking, the Rwanda plan is stalling, and returns are difficult and costly. We can therefore understand the government’s migration policies as political gesturing, of appealing to more right-wing constituents, rather than realistic action to curb small boat migration. Indeed, looking at the political context more broadly, and the Conservative party’s electoral ratings and immense asylum backlog, may provide more answers as to the timing of this immigration bill and its hardline stance.

Of course, if migrants who arrive in small boats are prevented from seeking asylum, and removals turn out impractical, people in need will end up in a state of limbo: neither protected, nor deported, and only more likely to fall prey to exploitation and underground networks.

First published on the LSE

Image credit: UK Home Office, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

About the author

Matilde Rosina

Matilde Rosina is Assistant Professor in International Relations at the University of East Anglia, LSE Fellow in International Migration and Deputy Director of the Centre for Italian Politics at King’s College London. She specialises in international migration and migration policy in Europe.

Oula Kadhum

Oula Kadhum is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at Lund University and a Fellow in International Migration at LSE’s European Institute. Her research explores religious and political transnationalism of diasporic communities in Europe and how they inform identity politics, nation-building, and oppositional movements in countries of origin and settlement.