As the Conservative Party’s election expenses are subject to much public criticism, UEA Student Will Temple argues that the Electoral Commission should have more powers.

British elections may not be saturated with money in the same way as the U.S., but a genuine concern still exists about the regulation of political party spending. These concerns have been brought to the fore by a recent ‘Channel 4’ investigation which revealed undeclared Conservative Party expenses in recent elections, which if had been declared, would have taken the party over spending limits for certain constituencies. Subsequently, this has forced an investigation by the independent regulatory body of British elections and political parties, the Electoral Commission to determine any wrongdoing. So far, this has led to the Commission advising the Crown Prosecution Service to apply for an extension to the legal time limit set for criminal convictions. It is thought that there are around 24 Conservative MPs accused of wrongdoing, who- if found guilty- could be disqualified as MPs, potentially resulting in the Conservatives losing their parliamentary majority. However, such actions would have more serious ramifications for both democratic fairness, as well as indirect impacts on public confidence, which should represent a far greater concern.

After being established in 2001, the Commission has seen its powers extended to include civil sanctions for political parties who break electoral laws. Currently, the maximum financial penalty the Commission can impose is a £20,000 fine for breaching financing regulations. However, central to the Commission’s review of the 2015 British General Election, was a recommendation for this upper- maximum fine threshold to be increased by Parliament. This is certainly an idea worth entertaining, as the current system has arguably encouraged- or rather failed to discourage- parties from seeking ‘loopholes’ in regulation. The manifestation of this has taken a myriad of forms, with the Liberal Democrats being embroiled in a financing scandal as recently as 2015, where it was reported that the party were advocating methods to hide names from official donor registers. This reveals an explicit unwillingness of political parties to ‘play by the rules’ to achieve a democratic ideal of fairness, as it clearly undermines guidelines set out in the ‘Political Parties, Elections and Referendum Act’, requiring all donations over £7,500 to be declared to the commission. Current sanctions are not robust enough. Increasing the investigative and sanctioning power of the Commission would provide a far more potent deterrent for parties who are actively seeking legislative loopholes.

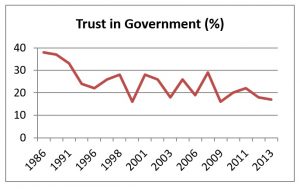

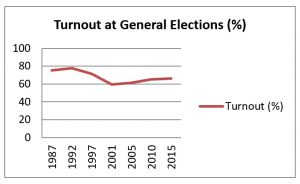

The behaviour of parties is damaging democracy because it impacts on public confidence. Research conducted into levels of public dissatisfaction with political parties has been measured in a multitude of ways, with arguably the most striking being conducted by ‘Transparency International’, which revealed that the British public deemed parties to be the country’s most corrupt institution. This is matched by a growing cynicism of politicians themselves, with only 22% of the British Public trusting politicians to tell the truth- making it one of the country’s least trusted professions. This loss of faith in political parties can be seen to correlate with falling electoral turnouts as shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

Whilst this is undoubtedly concerning, this does not represent a societal shift away from political action in general- but rather a rejection of political parties as a vehicle for democratic participation. This is shown through alternative, more direct means of political participation rising to prominence, such as signing petitions- the popularity of which has grown exponentially in recent years. Some have suggested that this may lead to a more representative democracy, however, this is problematic if it is replacing rather than supplementing traditional forms of participation. Therefore, in order to minimise the loss of public confidence in elected representatives, it is crucial that proper structures exist to coerce adherence to the legislature, whilst ensuring appropriate sanctions are in place for any transgressions. Although it has been suggested that financing reforms only have a marginal effect on voter confidence, it is clear that certain preliminary steps need to be implemented to prevent the further degradation of public confidence.

Ultimately, direct comparison with other similar states is difficult as the scale and forms of sanctions vary greatly. According to ‘IDEA’, 77.3% of European nations have fines as a method of sanctioning political parties for wrongdoing. However, the majority of these states (63.6%) also supplement these fines with the removal of public funding. This is certainly something which could be explored in the United Kingdom, as rather than imposing arbitrary fines for misbehaviour; the Commission could restrict the ‘short money’ paid to political parties, which often makes up a sizable chunk of an opposition parties’ income.

Despite this, it should be noted that raising the sanctioning power of the commission should not be seen as an end in itself, but rather a necessary catalyst for future, more ambitious campaign finance reform. Drawing on research pioneered by Pippa Norris, it can be suggested that in order for any reformation to be successful, the political will to implement and police changes is a necessary condition. Clearly, history has suggested that there is little appetite amongst British political parties for major reform to occur, due to parties benefitting from the maintenance of the status-quo. This means that undesired reform can lead to the manipulation of rules. Ultimately, this contradicts the reasons why such rules were implemented in the first place, as failure to adhere to set rules further undermines public confidence and results in a weakening of democracy. Therefore, it is important to recognise that whilst wholesale changes may be desirable, providing the Commission with the necessary regulatory structures is essential to prevent changes from becoming more damaging to public confidence in the short-term. Only once such structures exist, will it be possible to enact ambitious change to fully restore fragile levels of public trust and to rebuild our crumbling democracy.

Will Temple is a UEA student who studies the module Electoral Malpractice run by Toby James

Image Credit: Flickr

You describe the Electoral Commission as “independent”. Four of the ten Commissioners are appointments by the parties the Commission regulates. This was introduced in the Political Parties & Elections Act 2009 expressly to make regulation more sensitive to the needs of the parties and not over-zealous. Since then, as far as I am aware, all actions against electoral malpractice taken by the Commission have been in response to media coverage. The Commission is only one appointed Commissioner away from technically being a process of self-regulation by the political parties.