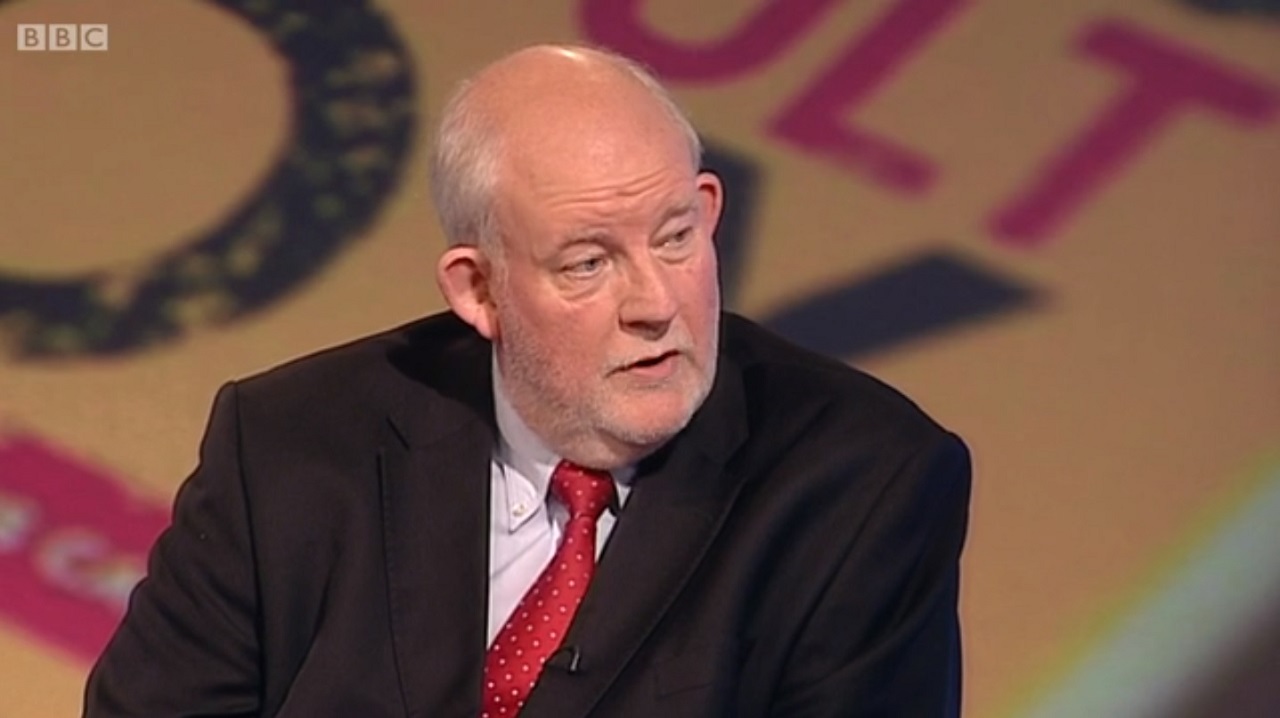

Peter Handley discusses Iain Duncan-Smith’s recent use of the word ‘Normal’ and the ‘common-sense’ about disabled people it assumes.

Earlier in the year I wrote about the conundrum I faced as a voter in the then upcoming General Election about whether or not I should vote. The sticking point for me were the views of each of the main political parties of disabled people. I pointed out that underpinning the ongoing ‘reforms’ of disability benefits are shared views of disabled people which split between that of feckless, scrounging, undeserving, good-for-nothings and those deemed deserving (the being some refer to as ‘super-crip’). The question I posed myself was: why should I vote for any party which held views such as these about a section of society I identify with?

As it turns out I did not vote, and I’m glad I didn’t. Iain Duncan-Smith’s latest musings on the nature of disabled people as ‘abnormal’ only vindicate suspicions that the main parties do not like disabled people very much, just as much as they explain a good deal about how he and his recent predecessors base their policy choices upon this very particular view about this section of humanity and what they really ‘are’. In the process of a self-congratulatory speech to the commons on the government’s record in getting disabled people back to work on September 8th Mr. Duncan-Smith spoke the following words:

“But the most important point is that we are looking to get that up to the level of normal, non-disabled people who are back in work”

Mr. Duncan-Smith’s remarks attracted much criticism in some sections of the media. And yet, to a significant extent, I suspect he was only articulating what one might call the ‘common-sense’ about disability and disabled people held by significant numbers of non-disabled people, even though those non-disabled people might- if asked to do so explicitly-articulate other less regrettable views about what disabled people ‘are’. What I am getting at is that conventional wisdom suggests that many people prefer not to think about disability because it is a ‘bad’ thing, an affliction, which reduces capacity to enjoy what political philosophers refer to as ‘the good life’. The prospect of disability is perceived quite simply to be too ghastly to contemplate for many; better that disability afflict someone else other than one’s own self or someone cares for. Like racism and sexism, what some disability scholars refer to as ableism is deeply embedded in modernity. Like racism and sexism, ableism is difficult to combat. To be sure, the idea of the ‘normal’ human being is particularly difficult to remove from the other items of intellectual furniture the modern individual carries around in his or her head given its apparently unimpeachable confirmation by medical science as a ‘natural phenomenon.

In fact, the term ‘normal’ is historically very recent and ‘normal’ people are made, rather than born. The term entered the French language in the early 1800s (‘normale’) and in English fairly quickly after that. It entered usage with the rise of statistics (political arithmetic, as it was called then) in the early years of the development of the social sciences to describe the regular, the usual, the typical, the ordinary, and the conventional. Thanks to the Victorians it was not much longer before the idea of the ‘normal’ began to take on more moral connotations. So, normal = good, deserving; abnormal = bad, undeserving. As social science developed some writers began to use the term’ deviance’ in connection with the ‘abnormal’. Disabled people- along with criminals, homosexuals, and so on- found themselves caught at the centre of this less than encouraging or helpful nexus, a nexus not of their own making, labelled ‘deviant’, ‘abnormal’.

Mr. Duncan-Smith’s use of the term ‘normal’ is thoughtless at best, irresponsible at worst, as well as highly divisive. Divisive? Why, yes. Despite the government’s rhetoric about social solidarity- being ‘in it together’ and the ‘big society’ – Ian Duncan-Smith’s language in conjunction with the policies he favours for disabled people are self- consciously geared to fracturing, dividing. Disability activists continue to contest the old labels of exclusion as they have done for the last forty years; for, as many among them argue, what has been made contains the possibility of being unmade with positive consequences. However, disability activists’ struggle has been and continues to be no easy task, given the deeply entrenched ‘common sense’ views about disabled people. One fears, though, we have not seen the last of this particular brand of ‘wedge’ politics because of the electoral dividends it clearly pays our representatives. Given this electoral success, one can only wonder what term will be deployed next by Ian Duncan-Smith and his successors to further marginalize disabled people as ‘abnormal’ others.

Image credit: Wikipedia

Dr Peter Handley is lecturer in the school if Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication Studies at the University of East Anglia