Although social media increasingly dominate our culture, a secondhand book convinces Professor Alan Finlayson that physical objects can be surprising and vital reminders of the very real connections we all have with each other.

A publisher recently expressed to me an anxiety no doubt widespread in his profession: that the printed book may soon disappear, overcome by the creative destruction of the e-book. The latter certainly appears to have advantages over paper and ink. Digitised books free you from something that can be heavy, clunky and easily damaged; you can easily search the text even when there isn’t an index. But efficiency is not the only thing that matters in life. You can’t pass on your e-book to a friend the way you can a paperback because all you hand over is a copy. When you pass on a paperback book you give something singular. No matter how many copies were printed, each individual edition of a book is a distinct object with its own unique history.

Here is a case in point.

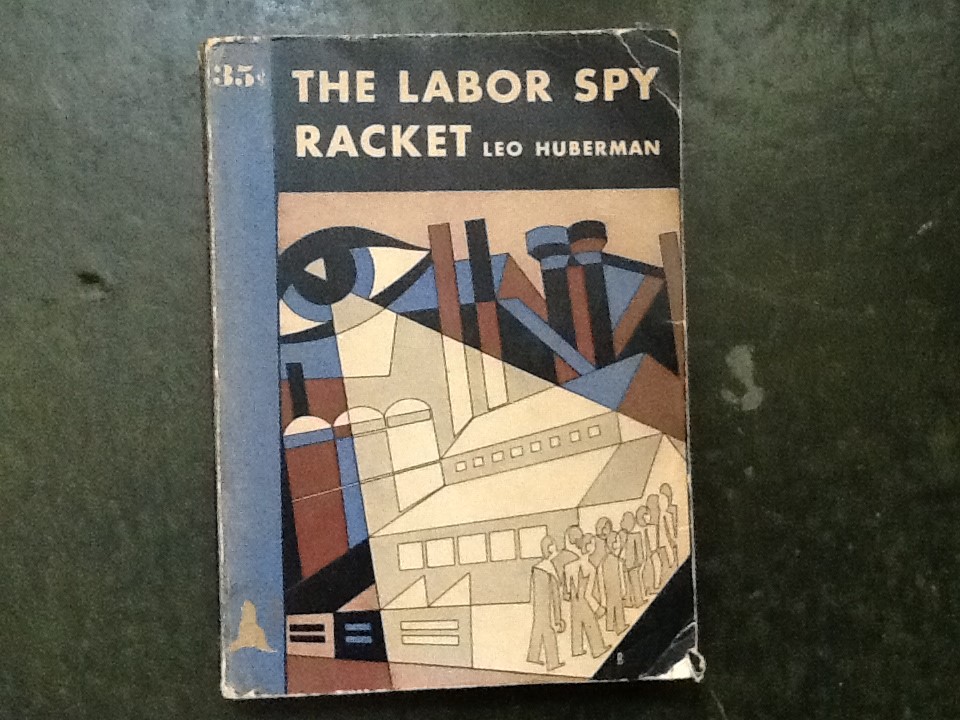

A friend recently gave me a number of books for which he no longer had room. Among many titles of interest one caught my eye because of the ‘constructivist’ style of its cover. Here is a picture of it sitting on my desk:

The New Jersey born author Leo Huberman was a Marxist, labour union activist and writer. His 1936 book Man’s Worldly Goods: The Story of the Wealth of Nations sold over half a million copies. He later founded The Monthly Review – a socialist magazine with an associated publishing imprint. Both are still going strong.

The Labour Spy Racket is about the infiltration of labour unions by corporate spies and the use of private police forces, such as the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, forcibly to suppress the American labour movement. The topic is timely; as I am writing this the BBC is reporting that the London Metropolitan Police spied on people campaigning for investigations into suspicious deaths in police custody.

If you want to, you can read Huberman’s book in full online here:

http://archive.org/stream/laborspyracket00huberich/laborspyracket00huberich_djvu.txt

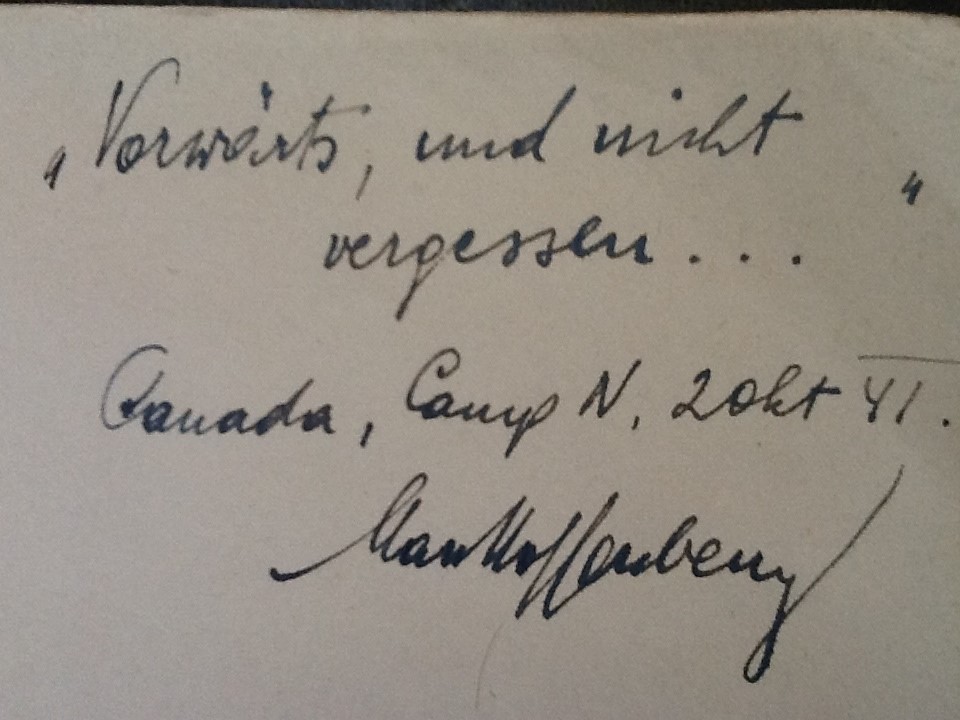

What you won’t get with the online version are the traces of previous readers. My copy has some notes in the margins and on the first page, there is this:

The first part says ‘Vorwärts und nicht vergessen’ which translates as ‘forward and don’t forget’. It is the opening line of Solidaritatslied – ‘Solidarity Song’ – by Marxist poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht and composer Hanns Eisler (who later wrote the national anthem for the German Democratic Republic). The song was written for the film Kuhle Wampe (‘Who Owns the World?’), the story of a working-class family struggling to survive in the aftermath of a terrible global financial crisis:

Forward, without forgetting,

Where our strength is now to be,

When starving or when eating,

Forward, not forgetting our solidarity.

You can hear Ernst Busch sing it here:

[youtube width=”420″ height=”315″ video_id=”3ieyxOdxQU0″]

The next words on the inscription are, as best I can tell, “Canada, Camp N, 2 Okt. 41”. The distributed intelligence of the internet enabled me to establish that the ‘N’ stands for Newington which is near Sherbrooke in South-East Quebec. There, on the site of unused property owned by the Central Railroad Company of Quebec, the British built an internment camp to house deported ‘enemy aliens’ – and there, on October 2nd 1941, someone inscribed their copy of a book about American Labor Unions.

Churchill’s Collar

At the start of World War II the British government had intended to avoid mass internments of the sort that had occurred in World War One. Instead it concentrated on identifying people thought to be Nazi sympathizers. But things were not going very well for Britain in 1940 and some of the newspapers (particularly those which had so recently been defending Hitler) were stoking anti-refugee feeling. The Daily Mail urged that ‘all refugees from Austria, Germany and Czechoslovakia, men and women alike’ should be removed ‘without delay to a remote part of the country’ and strictly supervised. The Sunday Chronicle (which in 1955 merged into the Empire News which in turn merged, in 1960, with The News of the World) claimed that ‘the letters readers send about Germans who are going free in their district would make your hair stand on end. Particularly the women’. Michael Foot, later leader of the Labour Party, protested in The Manchester Guardian ‘Why not lock up General de Gaulle?’ arguing that anti-Nazi and anti-Fascist refugees should be welcomed as valued allies.[1] Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940 and at his first cabinet meeting on May 11th announced a plan to, as he put it, ‘collar the lot’. Italians, Germans and Austrians (most of the latter Jewish refugees of the Nazis) were rounded up and eventually sent to Australia and to Canada.

My copy of The Labor Spy Racket must have once been with someone interned about one-hundred miles east of Montreal. They were German, presumably a Jewish refugee, and perhaps politically inclined. In his book Prisoners of the Home Front: A Social Study of the German Internment Camps of Southern Quebec, 1940-1946, Martin Auger records the worries of camp commanders that Communists were active amongst the internees who, as a consequence, became more demanding. They resisted the anti-semitism of some of the camp commanders, objected to being called ‘prisoners-of-war’ and, understandably, did not like being kept in a camp with actual, Nazi, prisoners-of-war. The internees were allowed, in some cases, to draw, and write and a few managed to take photographs. They also ran educational classes – perhaps it was there that books such as Huberman’s were given out as reading. Here, you can read a lot more about the camps and see photographs of life there: http://enemyaliens.ca/pdf/guide-eng.pdf).

When they were freed many of the refugees remained in Canada. Amazingly you can find online a digitised copy of a 1997 ex-internees newsletter. It details the incredible contribution they made to Canadian society and culture (see here). One of them, Eric Koch, became a successful broadcaster for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He had been about to sit his final exams for a Law degree at Cambridge University when he was arrested. He recounts his experiences here. Koch was in “Camp N” and so it is possible that he met whoever it was that once owned my copy of Huberman’s book. I do not know who that was. I cannot make out the final word in the inscription – it might be a name but I am not sure. No matter. At some point, somehow, with or without its owner, the book made its way from North America to the UK and eventually it came to me.

The Powers of Objects

Human beings are often compelled to grant objects a special power. Religious believers can be convinced that ‘relics’ of saints and martyrs have the power to heal. eBay is full of objects whose desirability is increased by the fact that they were signed, touched or once owned by someone famous. For £3500 you can buy a cheque signed by Marilyn Monroe and for £595 a small toy puppet theatre once owned by Elton John. In the UK people of all sorts make pilgrimages to museums and stately homes where they stop and wonder at things that once belonged to people who now exist for us only in school history books and BBC costume dramas.

All of this is certainly irrational. But I think it would be somewhat more irrational to believe that we could remove all such imagined enchantment from the things of the world and still be able to live in it. The political theorist and philosopher Hannah Arendt writes in her book The Human Condition,

Whatever enters the human world of its own accord or is drawn into it by human effort becomes part of the human condition…The objectivity of the world – its object- or thing-character – and the human condition supplement each other. Because human existence is conditioned existence, it would be impossible without things, and things would be a heap of unrelated articles, a non-world, if they were not the conditioners of human existence.

What she means, I think, is simply that things matter. We may feel or imagine ourselves to be isolated beings in a world that we must bend to our will. But actually we are intimately and inextricably wrapped up in all sort of things outside of ourselves which make the world possible for us. Arendt’s book begins with the successful launch of Sputnik, the first man-made satellite, and ends with the threat of nuclear annihilation. She is, I think, ultimately hopeful about the capacity of human beings to sustain themselves and each other in a web of meaningful relationships. But she is also worried by the way in which contemporary technology brings about a world where objects cease to exist ‘with’ us and become just ‘stuff’ intended for consumption and exchange, always a ‘means’ but with no actual ‘end’.

Furthering this thought another political theorist, Bonnie Honig, urges us to recognize the importance for democratic societies of public things such as ‘parks, prisons, schools, armies, civil servants, hydropower plants, electrical grids, and so on’. These matter, she says, not just because they provide ‘efficient’ services but also because they are the elements of a common life – things made by us to sustain us in that common life. A healthy democracy, she argues, is rooted ‘in common love for and contestation of public things’, of what they might be and of how best to care for them. She worries, however, that we are losing these to privatization and with them losing the things which give shape, structure and meaning to our common existence. You can hear her talk about this here.

From this perspective my copy of The Labor Spy Racket is a rather paradoxical object. It is a public expression intended to spread information and to mobilize people in political struggle. My particular copy of it, however, is a private possession. Yet it is only temporarily so. It has travelled some distance before getting to me and will, I am sure, travel somewhere else in the future. It has its own singular history which is contained within a larger collective history of empire and dominions, Fascism, Communism, racism, state and corporate domination. This is a history that is not yet over.

And what I know about the history of my book I know only because of the public things of the internet. Without leaving my private office I have been able to access pictures, stories and videos and even, thanks to the incredible public resource that is the National Archive, images of the cards on which British officials recorded the details of those they deported and those they years later readmitted to the UK. In this way the digital extends our reach. But its connectivity matters because it joins together people, things and objects which have a singular tangibility. And that is why things such as books must never wholly disappear. As I type this I have in sight a copy of a book that once was held in the hands of another. When I read it I read not only the words that Leo Huberman wrote but the very same black type once looked on by a refugee in an internment camp thousands of miles away from where I am now. The object connects us – literally not metaphorically or virtually – across that space. It also connects us across time, joining the past to my present and pointing to a future in which someone else will read the book for themselves: vorwärts und nicht vergessen.

Alan Finlayson is Professor of Political & Social Theory at the University of East Anglia

[1] These quotations are taken from British Policy and the Refugees, 1933-1941 by Yvonne Kapp and Margaret Mynatt, Routledge, 1977, pp. xi-xii.