The UK government’s proposal for a “red card procedure” for national parliaments to stop EU policy proposals would have affected less than two percent of votes in the EU Council of Ministers — and that’s assuming governments lose the plot, argue Sara Hagemann, Chris Hanretty and Simon Hix.

Source: https://c2.staticflickr.com/8/7647/16685723418_5c81136bc2_b.jpg

Earlier this month the president of the European council, Donald Tusk, proposed several measures aimed at addressing British concerns about continued EU membership. One of these measures was a new “red card” procedure for national parliaments, whereby 55% of parliaments could challenge EU proposals, with a strong presumption that they would be withdrawn unless amended to meet parliaments’ concerns.

Most discussion of the red card idea has compared it to the existing yellow and orange card procedures, which allow parliaments to register their discontent. These procedures have lower thresholds (one-third of parliaments in the case of the yellow card, half in the case of the orange card), but have rarely been used. The red card procedure is likely to suffer the same fate.

Suppose that any proposal opposed by a member state government is also opposed by the parliament of that member state, and vice versa. It follows that any proposal opposed by 55% of parliaments will also be opposed by 55% of member state governments. Under EU decision-making rules, any proposal that is opposed by 55% of member state governments will be rejected in the European council. Hence, any proposal that would be blocked by the new procedure would have been blocked in the council anyway.

However, this analysis relies on the assumption that EU governments’ positions are the same as those of their parliaments. The parliament of a member state will often have the same view of European legislative proposals as the government of that state, either because the government enjoys the support of a majority in the parliament, or because both government and parliament are ultimately responsible to national voters, who will have their own views on European integration.

It is not true, though, that governments and parliaments always agree. For example, there are at least four ways disagreement can occur:

Bicameralism: some governments are not responsible to the upper chambers of their parliaments, who might have divergent views (Under the red card procedure, each chamber gets a vote, except in unicameral systems, where the sole chamber gets two votes.)

Minority government: governments might be responsible to a chamber of parliament, but not have the support of a majority in the parliament

Intra-government conflict: the government as a whole may be responsible to the parliament, but individual ministers (including prime ministers) may have positions that do not enjoy support.

Backbench conflict: the government may depend for its support in parliament on backbenchers who have very different views on Europe.

Here we concentrate on the first two of these possibilities. Although intra-government and backbench conflict are important, we think it unlikely that ministers or governments would be so maladroit as to permit parliament to send such a visible signal of opposition through use of the red card procedure. Such a government would not be last long.

To assess whether bicameralism and minority government open up a space for the red card procedure, we proceed as follows:

First, we concentrate on the years since 2009 (when the Lisbon treaty was implemented and further extended the qualified majority voting rules) and identify all 703 measures that achieved a qualified majority in the council between 7 July 2009 and 3 December 2015, and count the votes of the parliaments of the member states who opposed the measure.

Second, we identify those member states that supported the measure, had a bicameral system, and where the government lacked a majority in the upper chamber. For these countries, we assume the upper chamber opposes the motion and votes accordingly.

Third, we identify those member states that supported the measure and had a minority government. For these countries, we assume the majority of parliament opposes the motion and votes accordingly. In systems that are both bicameral and have the minority government, we assume both chambers of parliament vote in opposition to the measure.

Finally, we add up the votes from the first to the third stages, and ask whether the measure would have been opposed by 55% of national parliaments.

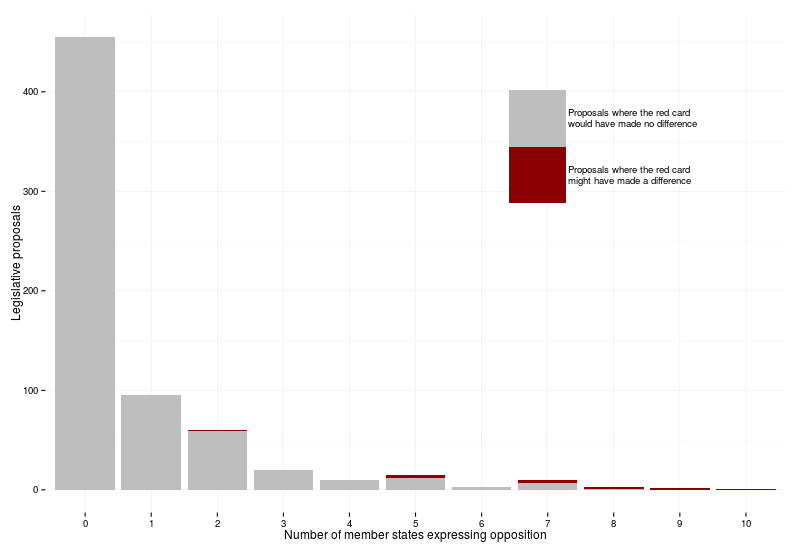

These are favourable assumptions for the red carpet procedure, yet applying them suggests the proposal could only have made a difference in nine (1.3%) out of 703 votes(see figure 1). This does not mean the red card would in fact have made a difference had it been in place: upper houses can agree with governments, and minority governments need not always face the opposition of parliamentary majorities. This figure should therefore be interpreted as an upper limit of the red card.

However, this figure might not represent an upper limit if votes are a poor guide to what member states really think- for example, if an observed voting consensus in the council is in fact “in the shadow of a vote”. To address this issue, we can repeat the above exercise using member states’ statements in anticipation of a vote. Member states often use such statements to signal opposition to a measure, without subsequently voting against the measure.

We therefore interpret every member state statement as de facto opposition to a proposal, equal to if it had been a vote. This changes slightly the number of proposals that achieved a qualified majority, from 703 to 674. Nevertheless, when we apply the same assumptions as above, using member state statements as if they were votes, we find that the red card would only have made a difference in 12 (1.8%) out of 674 votes (see figure 2).

In short, our analysis suggests that the red card would therefore only ever be in a play under 2% of council votes, even assuming that upper chambers systematically go against minority governments. In practice, we suspect the red card will be only ever be used once or twice over the next 20 years. It would therefore make very little difference to decision-making in the EU.

If the red card is recognised to make little difference, UK voters may think less favourably of the deal David Cameron has all but secured, and thus may be less likely to vote for continued British membership.

However, it is important for voters who care about the issue of “sovereignty” – which is the headline that the role of national parliaments and the red card procedure have been presented under- to understand the reasons why the red card proposal is of limited value.

The red card makes very little difference because decision-making in the EU is generally characterised by an extensive set of checks and balances where national politicians already have a number of ways to influence policy proposals: they can do so through their governments in the council and through their embassies (permanent representations) in Brussels; through their nationally elected members of the European parliament; and through their senior officials in the European commission.

It is difficult to see what a veto to a group of national parliaments should add to the process as their opinions would already be voiced through these other channels. If the red card is never put to use, it may not be because the referees are timid, but because there is already a high level of fair play.

A full list of the proposals that might have been affected by the red card procedure can be found here.

This post originally featured on the Guardian’s European Union blog

Image Credit: Flickr

Sara Hagemann is assistant professor in European politics at London School of Economics (LSE) and a senior fellow in the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) UK in a Changing Europe programme.

Chris Hanretty is reader in politics at the University of East Anglia.

Simon Hix is Harold Laski professor of political science at LSE and senior fellow on the ESRC’s UK in a Changing Europe programme